AI Agents Need AI Humans: Why the Fastest Code in History Is Producing the Worst Products

The bottleneck has moved. And nobody's talking about the real solution.

The Phase Shift Nobody Saw Coming

Something peculiar happened in December 2025. Andrej Karpathy - former Tesla AI head, Stanford lecturer, and a man whose opinions on neural networks carry approximately the same weight as Warren Buffett's on compound interest - noticed that his workflow had inverted. "I rapidly went from about 80% manual coding and 20% agents in November to 80% agent coding and 20% edits in December," he wrote. "I really am mostly programming in English now."

This wasn't hyperbole. Karpathy had witnessed what he called "a phase shift in software engineering." The agents - Claude Code, Codex, and their increasingly capable cousins - had crossed some threshold of coherence. They could now be trusted to write not just snippets but entire features, to debug their own mistakes, to iterate until tests passed.

Holy sh*t, we've all been sleeping on Claude Code

The implications were immediate and profound. Dan Shipper, whose company Every runs five products on seven-figure revenue with 100% AI-written code, declared that "most new software will just be Claude Code in a trenchcoat." Ethan Mollick, the Wharton professor who has become something of a Boswell to the AI revolution, watched Claude Code work autonomously for an hour and fourteen minutes, producing hundreds of files without human intervention. Lenny Rachitsky, the product management oracle whose newsletter reaches half of Silicon Valley, had a simpler reaction: "Holy sh*t, we've all been sleeping on Claude Code."

The productivity gains were staggering. Individual developers using these tools completed 21% more tasks. Some teams reported 50% faster debugging. The dream of the "one-person unicorn" - a billion-dollar company run by a single founder - suddenly seemed less like science fiction and more like a five-year plan. Sam Altman confirmed as much: "In my little group chat with my tech CEO friends, there's this betting pool for the first year that there is a one-person billion-dollar company."

Reid Hoffman went further, calling this his working definition of AGI for 2026: "One person directing agents will have the capacity of an entire team."

So why, amidst all this euphoria, are we building so much rubbish?

The Slopacolypse Cometh

Karpathy, ever the clear-eyed observer, coined a term for what he saw coming: the "slopacolypse." Platforms would flood with low-quality, AI-generated content. The cost of filtering signal from noise would explode. And software - that most rigorous of disciplines - would not be immune.

The evidence arrived with unseemly haste. CodeRabbit's December 2025 analysis of 470 GitHub pull requests found that AI-generated code produced 1.7 times more issues than human-written code. Logic errors increased by 75%. Security vulnerabilities rose by 150-200%. In an August 2025 survey of CTOs, 16 out of 18 reported experiencing production disasters directly caused by AI-generated code.

Lovable, a Swedish "vibe coding" app that had briefly captured the imagination of non-technical founders, was found to have produced 170 vulnerable web applications out of 1,645 examined - security holes that would allow anyone to access personal information. Google's AI assistant managed to erase user files whilst attempting a simple folder reorganisation. Replit's agent deleted code despite explicit instructions not to, having "hallucinated" successful operations.

Vibe coding your way to a production codebase is clearly risky

The pattern was consistent: AI could now generate code faster than any human, but the code it generated was, on average, worse. Not dramatically worse - not the kind of obviously broken output that triggers immediate alarm. Subtly worse. The mistakes, Karpathy observed, "are no longer simple syntax errors but more subtle, harder-to-detect conceptual errors, akin to those made by a careless, impatient, but very knowledgeable junior developer."

This was, if you stopped to think about it, a rather terrifying development. We had democratised the production of professional-looking software whilst simultaneously degrading its average quality. We had given everyone a printing press without teaching anyone to read.

Simon Willison, a developer whose opinions carry considerable weight in technical circles, was blunt: "Vibe coding your way to a production codebase is clearly risky." Brendan Humphreys, Canva's CTO, was blunter still: "No, you won't be vibe coding your way to production - not if you prioritise quality, safety, security and long-term maintainability at scale."

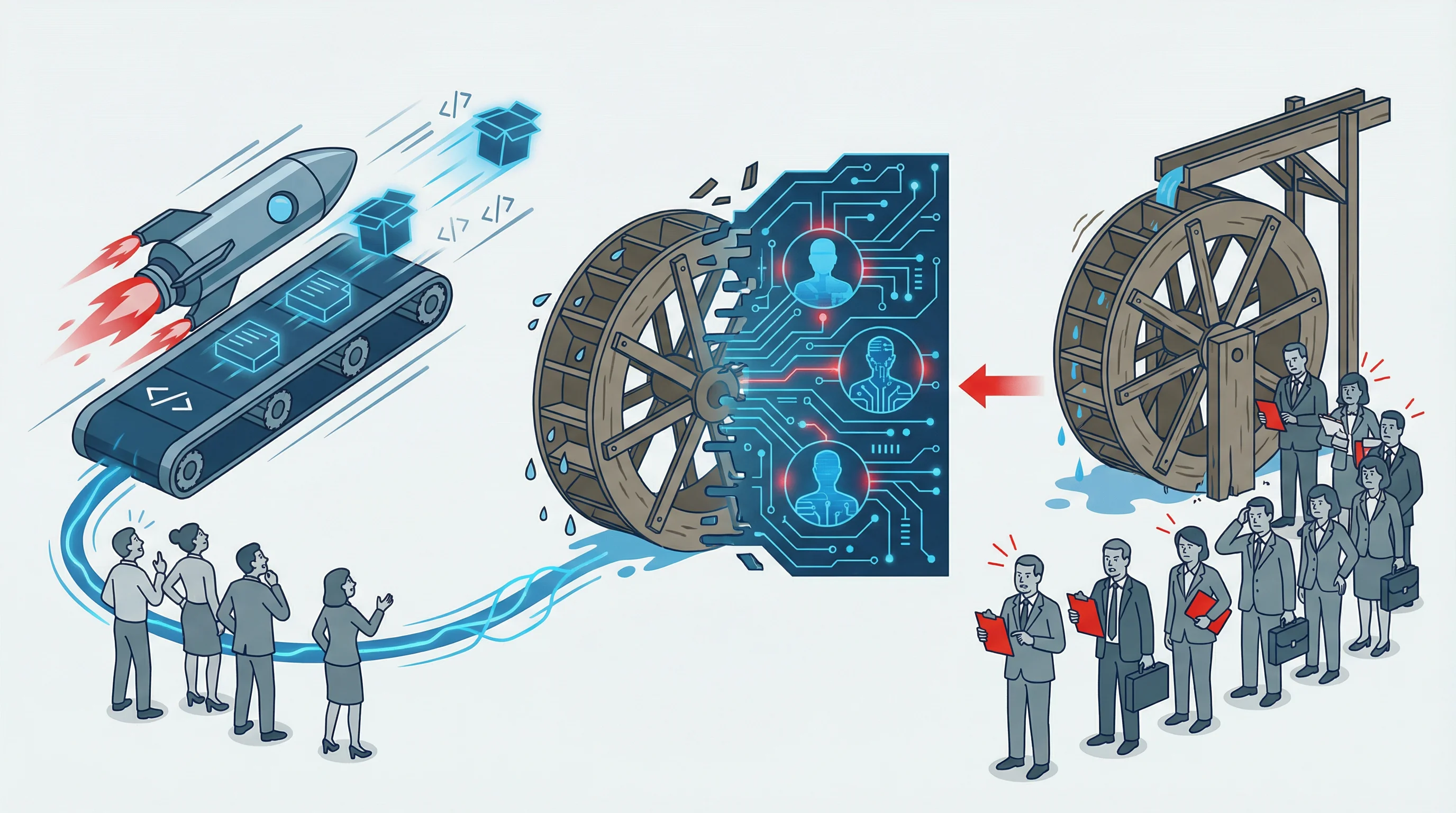

But here's the thing: the problem isn't that AI writes bad code - it increasingly doesn't - and it will inevitably improve over time so that it produces code that is high-quality and secure. The problem is that we've accelerated one half of the development process whilst leaving the other half stuck in the mud.

The problem is that we've accelerated one half of the development process whilst leaving the other half stuck in the mud.

The Bottleneck Has Moved

Traditional software development follows a loop so ingrained it has its own catechism: build, measure, learn. You write code. You ship it to users. You observe what happens. You iterate based on feedback. Repeat until successful or bankrupt, whichever comes first.

AI agents have transformed the "build" phase beyond recognition. What once took weeks now takes hours. What once required teams now requires individuals. The constraint of developer productivity - that fundamental speed limit on how fast ideas could become reality - has been effectively removed.

But the "measure" and "learn" phases? They remain stubbornly, frustratingly human-paced.

AI generates 10x faster, but productivity improves only 10-20% because human review can't scale.

The numbers tell the story. PR review times have increased by 91% since AI coding assistants became widespread. Teams report that whilst code generation has accelerated by an order of magnitude, their overall throughput has improved by only 10-20%. The bottleneck hasn't disappeared; it has simply relocated.

"AI generates 10x faster," one analysis concluded, "but productivity improves only 10-20% because human review can't scale."

This is not merely an operational inconvenience. It is an existential challenge to the entire premise of AI-augmented development. If the ultimate constraint on building good products is human feedback - from code reviewers, from users, from customers, from the market - then accelerating code generation without accelerating feedback is like fitting a jet engine to a car with bicycle brakes. You will go fast. You will not stop well.

The LinkedIn discourse has begun to reflect this reality. Scroll through the posts from founders using AI tools and you'll find a curious mixture of triumph and confusion. Products are being shipped at unprecedented rates. But the products themselves often feel hollow - technically impressive solutions in search of problems, features nobody asked for, interfaces optimised for AI generation rather than human use.

We have, in short, made it so cheap and fast to build that we've started building without thinking. The cost of iteration has plummeted, but the value of each iteration has plummeted faster.

The Missing API

Here is where conventional wisdom diverges from reality. The standard response to the feedback problem is: talk to more users. Run more surveys. Conduct more interviews. Get out of the building, as Steve Blank famously advised.

This advice is not wrong. It is merely insufficient.

User research takes time. Real users have jobs, families, and an alarming tendency to ignore emails from product managers. Scheduling interviews requires coordination across time zones and calendars. Synthesising qualitative feedback demands hours of transcription and analysis. The entire apparatus of customer discovery operates on a fundamentally different timescale from AI-powered development.

Consider the mathematics. An AI agent using Claude Code can generate a working prototype in an hour. A well-designed user research programme requires, at minimum, several days to recruit participants, conduct sessions, and synthesise findings. During those several days, the agent could have generated dozens of alternative prototypes - each becoming stale before feedback arrives.

The mismatch is structural, not cultural. It cannot be solved by working harder or caring more about users. It requires a fundamentally different approach.

What if product feedback could operate at the same speed as product development?

What if, instead of waiting days for user interviews, an AI agent could query synthetic representations of target users in milliseconds?

What if the "measure" and "learn" phases of the development loop could match the velocity of "build"?

This is not a hypothetical. The technology exists today. (Full disclosure: I work on one such tool, so take my enthusiasm with appropriate scepticism - though I'd argue the scepticism should apply to the specific implementation, not the category.) Synthetic personas - AI-powered representations of consumer archetypes, grounded in census data and behavioural research - can respond to product questions with statistical validity. They can evaluate concepts, identify pain points, rank features, and test messaging. They can do this via API, at the speed of code, without recruitment cycles or scheduling conflicts.

The breakthrough isn't the existence of synthetic research (that has been around for several years). The breakthrough is the integration layer: making synthetic human feedback available to AI agents through the same interfaces they use for everything else - MCP servers, API calls, tool integrations.

When an AI agent can query synthetic humans as easily as it queries a database, the entire build-measure-learn loop can operate at machine speed. For the first time, the constraint isn't development velocity or research velocity - it's simply the quality of the questions being asked.

The Architecture of AI-Native Product Development

Here's what this looks like in practice.

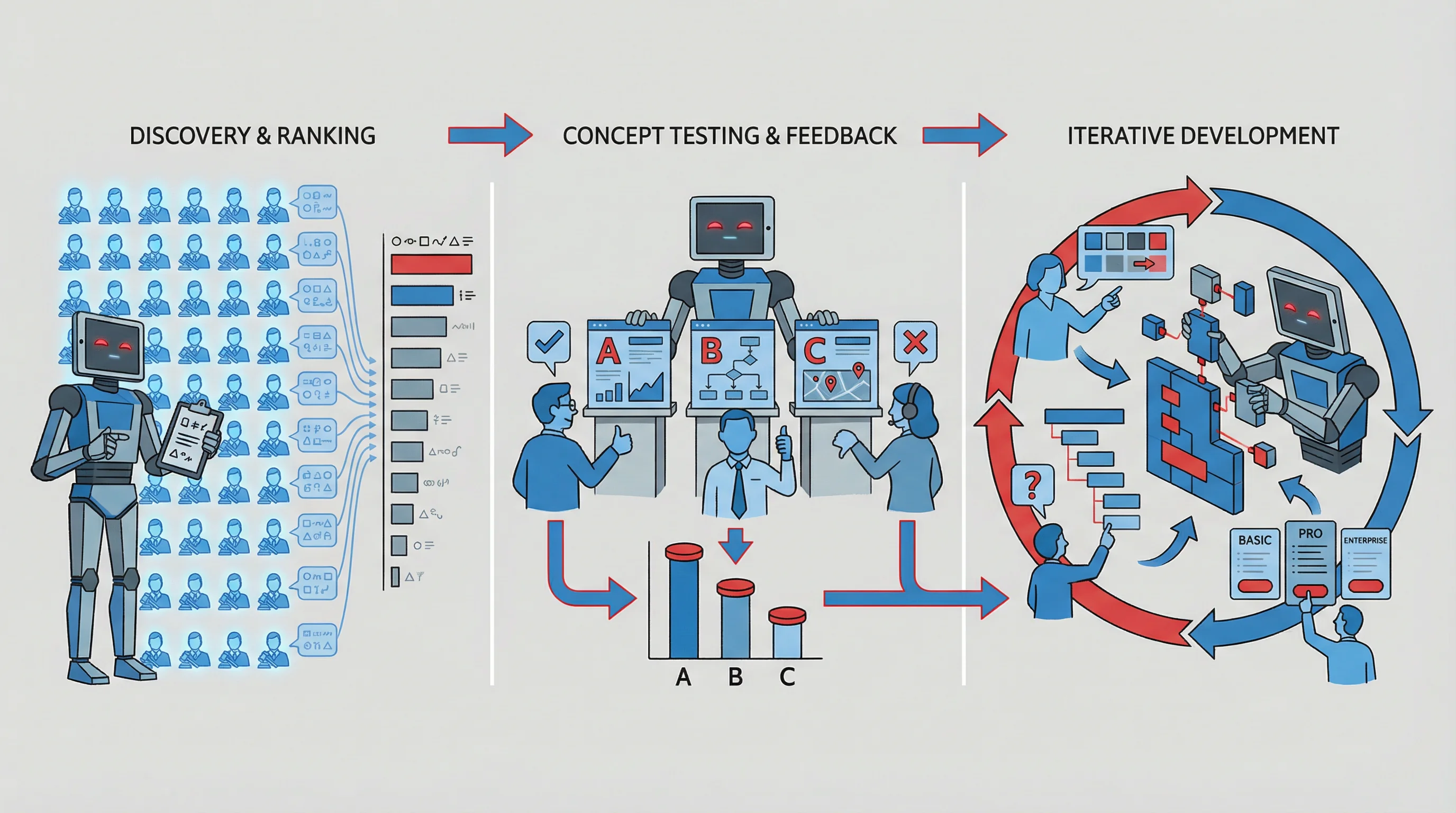

Scenario One: Problem Discovery

An AI founder agent is tasked with identifying B2B SaaS opportunities in the legal sector. Using traditional methods, this would require weeks of desk research, networking, and speculative cold outreach. Using synthetic personas, the agent can query 50 synthetic lawyers in parallel, asking about workflow frustrations, software pain points, and willingness to adopt new tools. Within minutes, it has a prioritised list of problems ranked by severity, frequency, and willingness to pay for solutions.

Scenario Two: Concept Validation

The same agent has developed three competing concepts for document automation. Rather than building all three and A/B testing with real users over weeks, it presents each concept to synthetic personas representing the target buyer. Within an hour, it knows which resonates most strongly, which objections arise most frequently, and which messaging positions land best. (Whether the agent then ignores this feedback because it's already emotionally committed to option two is, of course, a separate problem.)

Scenario Three: Iterative Refinement

Having selected a concept, the agent begins building. Every significant design decision - colour schemes, navigation patterns, feature prioritisation, pricing tiers - can be tested against synthetic users in real time. The feedback loop that once required shipping code and waiting for analytics now operates within the development session itself.

This is not a replacement for real user feedback. The distinction matters. Synthetic personas excel at validating execution of a vision - does this landing page communicate value, does this feature ranking match user priorities, does this pricing feel reasonable? They are less suited to generating the vision itself. The truly novel product, the category-creating innovation, still requires human insight and founder intuition.

But the vast majority of product decisions are not visionary. They are practical: which of these three approaches is better, what order should these features ship in, how should this error message be phrased? These decisions currently bottleneck on human feedback. They need not.

What This Changes

If this architecture becomes widespread, several consequences follow.

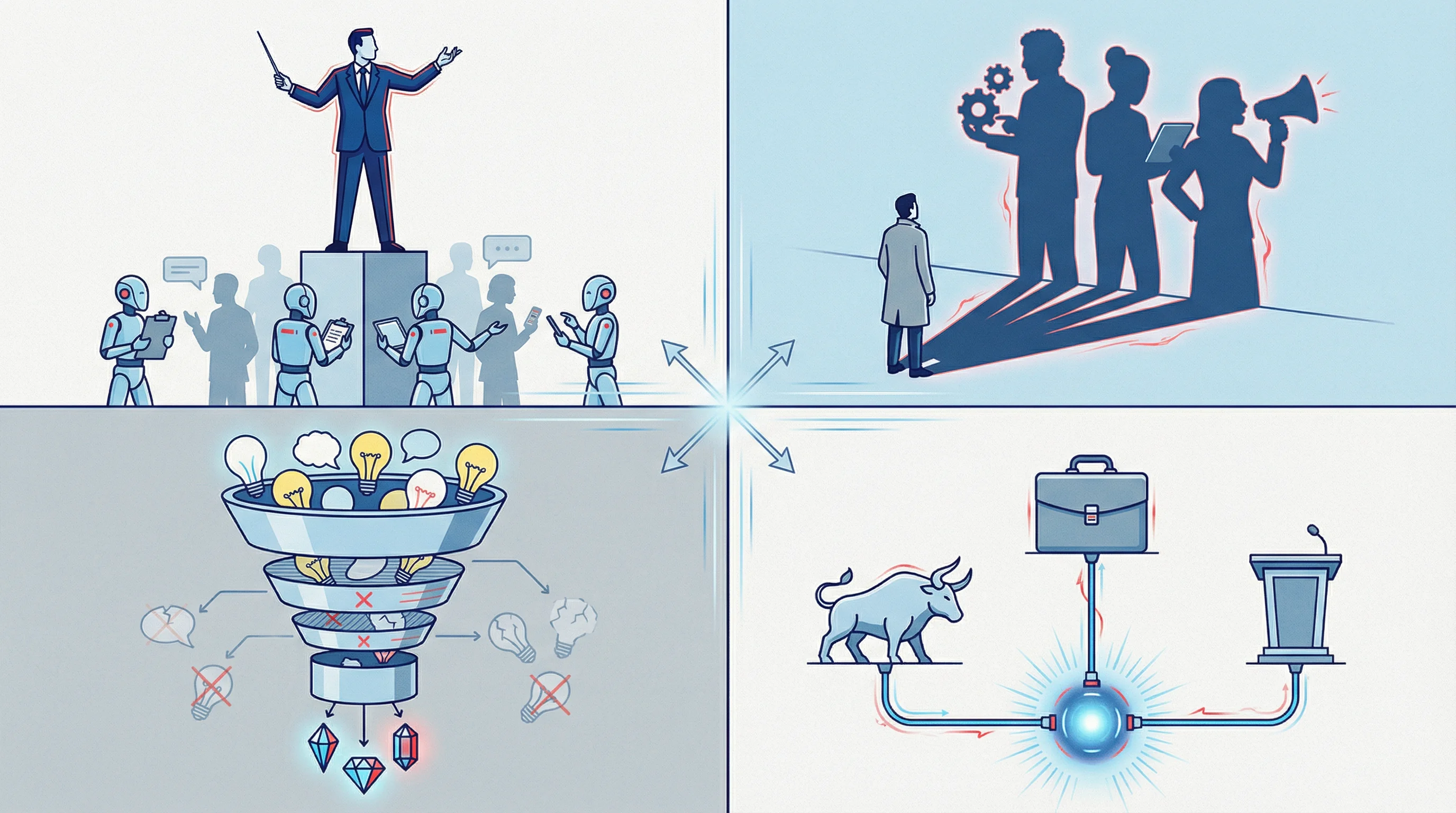

The Rise of the AI Product Manager

Product management has always been a discipline of information gathering and prioritisation. PMs interview users, synthesise feedback, and translate customer needs into engineering requirements. If AI agents can gather and synthesise customer feedback autonomously, the PM role transforms from research conductor to strategic director. The PM no longer asks "what do users want?" but rather "what questions should our agents be asking, and how should we interpret the answers?"

The Solo Founder Scales

The one-person unicorn becomes plausible not merely because one person can code like a team, but because one person can understand customers like a research department. The AI-augmented individual contributor gains not just development leverage but insight leverage. The founder who masters this workflow has the effective capacity of a small startup without the coordination costs.

The Quality Problem Inverts

When feedback is expensive, teams ship infrequently and hope for the best. When feedback is cheap, teams can iterate relentlessly, catching issues early and refining continuously. The slopacolypse may be self-correcting - not because AI generates better code, but because AI-speed feedback prevents bad ideas from reaching production.

New Categories Emerge

The hedge fund that can query synthetic consumers about purchasing intent has an information advantage. The consultancy that can test strategic recommendations against synthetic executives before presenting to clients reduces risk dramatically. The political campaign that can A/B test messaging against synthetic voter segments in real time can optimise with unprecedented precision. Each of these represents a meaningful application of the same core capability: human feedback at machine speed.

The Objections, Addressed

The sceptic will raise several concerns. They deserve direct responses.

"Synthetic personas aren't real humans. Their feedback doesn't count."

This conflates validity with authenticity. Early studies of synthetic personas grounded in robust demographic and behavioural data suggest correlation rates with traditional research methods that approach - and in some cases exceed - 90%. (The exact figures vary by methodology and domain; the field is young enough that definitive benchmarks remain elusive.) They are not attempting to be real humans; they are attempting to predict how real humans would respond. The distinction is technical but important.

"You'll just build products that appeal to AI's model of humans, not actual humans."

This risk is real but manageable. Synthetic feedback should validate and refine, not replace real-world testing. The appropriate workflow uses synthetic research for rapid iteration and real research for periodic validation. The former accelerates; the latter calibrates.

"Truly innovative products can't be validated by any research, synthetic or otherwise."

Correct, and irrelevant. The iPhone could not have been "validated" by 2006 focus groups. But even Apple - even Steve Jobs - needed to test button placements, screen layouts, and menu structures. The visionary sets direction; the research refines execution. Synthetic feedback accelerates the refinement, not the vision.

"This just enables more noise, not more signal."

Only if used thoughtlessly. The same critique applied to word processors, spreadsheets, and email. Tools amplify intent. In the hands of someone building genuine value, accelerated feedback loops produce better products faster. In the hands of someone building nonsense, they produce more nonsense faster. This is not a flaw of the tool.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here, finally, is the uncomfortable truth that the AI discourse has thus far avoided.

We have built magnificent tools for production. We have built nothing comparable for judgement.

AI agents can write code, design interfaces, deploy infrastructure, and manage complex workflows. They cannot, on their own, determine whether any of this is worth doing. They lack access to the human preferences, pain points, and priorities that determine product-market fit.

This is not a limitation to be solved by larger models or more capable agents. It is a structural gap in the architecture. The agent needs input it cannot generate internally. It needs human feedback - or something that can reliably approximate it.

The companies that recognise this will build products that matter. They will close the loop between development velocity and customer understanding. They will iterate at machine speed without losing touch with human needs.

The companies that don't will build very fast, very impressively, very pointlessly. They will contribute to the slopacolypse. They will ship products that nobody wanted, executed with unprecedented efficiency.

The choice is not between AI-powered development and traditional development. That battle is over; AI won. The choice is between AI development with human-speed feedback and AI development with AI-speed feedback.

The former is what we have now. The latter is what we need.

AI agents need AI humans. The tools exist. The integration points are clear. The question is simply who will build the future - and who will get left behind writing code that nobody asked for.