Sixty-eight percent of sales opportunities are competitive. That statistic, from Klue's competitive intelligence research, should haunt every product marketer who has ever sent a sales team into a deal without adequate competitive preparation. Two thirds of the time, your prospect is actively comparing you to someone else. And in those moments, the outcome depends less on your product's objective merit than on how effectively your team can articulate why you win, neutralise your competitor's claims, and ask the questions that expose the gaps your rival would rather not discuss.

This is the domain of competitive intelligence. It is, by common consensus, one of the most impactful functions in product marketing. Companies with well-maintained competitive battlecards report winning twenty percent more competitive deals. Yet the qualitative layer of CI, understanding how customers actually perceive your competitors, remains one of the hardest to obtain. The tools exist for monitoring competitor websites, tracking pricing changes, and aggregating review site data. What they cannot tell you is what goes through a buyer's mind when your competitor makes their pitch.

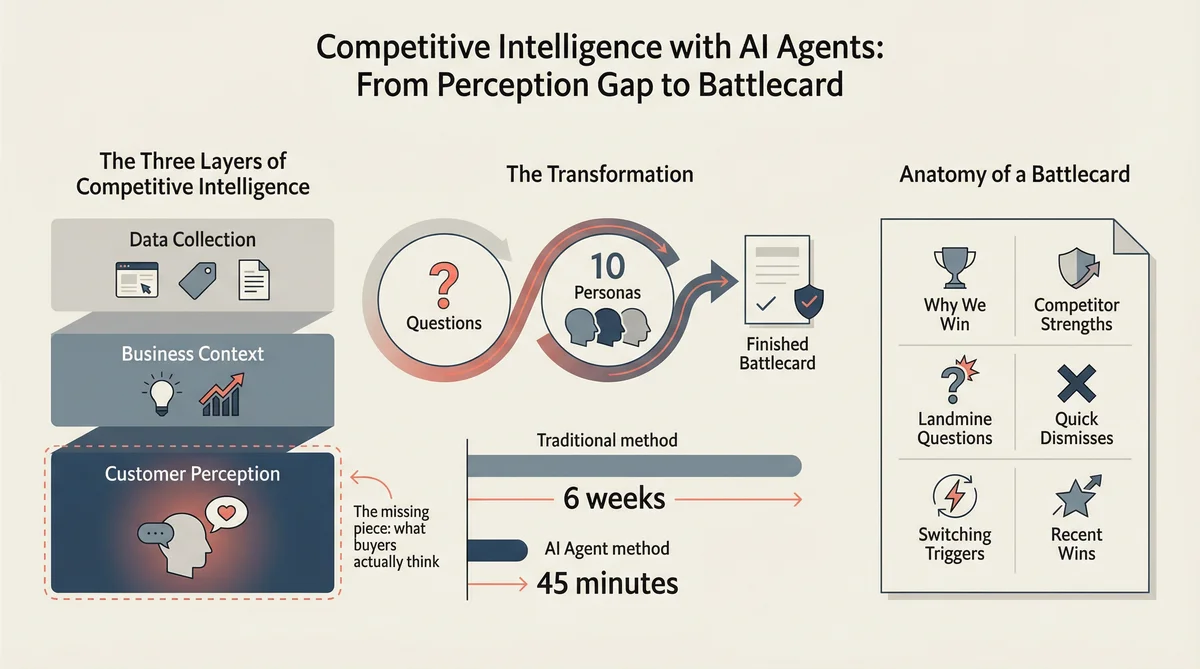

This article explains how to build a complete competitive intelligence programme using Ditto, a synthetic market research platform with over 300,000 AI personas, and Claude Code, Anthropic's agentic development environment. The output is a finished competitive battlecard, complete with win themes, landmine questions, quick dismisses, and a switching trigger map, produced in approximately forty-five minutes rather than the four to six weeks typical of traditional competitive research.

The Three Layers of Competitive Intelligence

Modern CI operates across three distinct layers, each progressively harder to obtain:

Layer 1: Data Collection. Automated monitoring of competitor websites, pricing, job postings, press releases, social media activity, app store reviews, and regulatory filings. Tools like Klue and Crayon excel here. This layer tells you what competitors are doing.

Layer 2: Business Context. Translating raw data into actionable insight. A competitor just hired twelve engineers in machine learning. A competitor's pricing page now emphasises a free tier that did not exist last quarter. A competitor's CEO just published a thought piece on vertical SaaS. This layer tells you what competitors are planning.

Layer 3: Customer Perception. How buyers actually perceive your competitor. What they believe. What they doubt. What would trigger a switch. What would prevent one. This layer tells you what the market thinks about your competitor, which is the only intelligence that matters when your sales rep is sitting across from a prospect who just had a demo with the other side.

Layers 1 and 2 are well served by existing tools. Layer 3 is where most CI programmes fall silent. Traditionally, the only way to obtain qualitative competitive perception data is through win/loss interviews: conversations with buyers who recently chose you or your competitor. These are notoriously difficult to arrange. Customers who chose your competitor are reluctant to speak with you. Those who chose you tend to tell you what you want to hear. The sample sizes are small. The cycle time is long. Best practice is to conduct win/loss interviews quarterly, targeting late-stage deals, with at least ten interviews per cohort to identify reliable patterns. Most teams manage fewer than five per quarter, if they manage any at all.

Ditto fills the Layer 3 gap. Its synthetic personas provide qualitative competitive perception at the speed of an API call, with sample sizes you choose and demographic filters you control. It does not replace win/loss interviews with real customers. It provides a continuous baseline of competitive perception that supplements the sporadic signal from actual buyer conversations.

Anatomy of a Competitive Battlecard

Before discussing how to generate one, it is worth establishing what a good competitive battlecard actually contains. The Product Marketing Alliance and competitive intelligence practitioners broadly agree on six essential sections:

Why We Win: The three to four most compelling reasons customers choose you over this specific competitor, supported by customer evidence. Not features. Outcomes.

Competitor Strengths: An honest assessment of where the competitor genuinely excels, paired with how to respond when a prospect raises these points. Sales reps who pretend competitors have no strengths lose credibility instantly.

Landmine Questions: High-impact questions that highlight competitor gaps without sounding adversarial. "Have you asked them about X?" is more effective than "They can't do X." These are the battlecard's most valuable asset.

Quick Dismisses: One to two sentence rebuttals for the competitor's most common claims. When a prospect says "But they told me they can do Y," your rep needs a concise, credible response.

Switching Triggers: The events, frustrations, or changes that create openings. A competitor raising prices, shipping a buggy release, losing a key integration partner, or failing an audit. When these events occur, your outbound should be ready.

Recent Wins: Specific examples of deals won against this competitor, with the industry, use case, and deciding factor. Social proof that is contextually relevant to the prospect's situation.

The ABC Framework for battlecard quality is instructive: Accuracy (one inaccuracy destroys seller trust and the card gets binned), Brevity (one page maximum, scannable in sixty seconds), and Consistency (standardised format across all competitor cards so reps know where to look). A beautifully detailed ten-page competitor dossier is less useful than a sharp one-page battlecard because no one reads it during a live call.

The Perception Gap: What CI Tools Miss

Here is the fundamental problem. Klue can tell you that Competitor A changed their pricing last Tuesday. Crayon can tell you that Competitor B published fourteen blog posts about AI this quarter. G2 reviews can tell you that customers give Competitor C 4.2 stars for ease of use. None of these sources can tell you the following:

When a prospect hears Competitor A's core claim, do they believe it?

What would actually trigger a customer to switch away from Competitor B?

If a buyer is comparing you to Competitor C, what is the single deciding factor?

Which of your competitor's "strengths" do customers genuinely value, and which are just features they do not care about?

What questions would expose the gap between your competitor's marketing and their reality?

These are the questions that win and lose deals. They are also the questions that a seven-question Ditto study can answer in thirty minutes.

The Seven-Question Competitive Perception Study

This study design has been refined across fifty-plus production studies. Each question targets a specific competitive intelligence need. Claude Code designs the study with your specific competitors and market context, Ditto recruits matching personas, and Claude Code synthesises the responses into a finished battlecard.

Question 1 (Brand Awareness and Associations): "When you think about solutions in [category], which brands or tools come to mind first? What do you associate with each?"

This establishes the competitive landscape from the customer's perspective. The brands they name first are your actual competitors, regardless of what your internal competitor list says. The associations they volunteer reveal positioning perceptions that are often wildly different from each competitor's intended positioning.

Question 2 (Head-to-Head Decision Drivers): "You are evaluating [your product] against [Competitor A]. What would make you lean toward one or the other?"

This is the core battlecard question. The factors personas cite as decision drivers become your "Why We Win" section when they favour you, and your "Competitor Strengths" section when they do not. The language they use becomes the language your sales team should use.

Question 3 (Competitor Strengths and Weaknesses): "What is the one thing [Competitor A] does really well? What is the one thing they do poorly?"

Forcing a single strength and single weakness produces sharper, more actionable insight than asking for a general assessment. The strength identifies where you should not compete head-on. The weakness identifies where your landmine questions should aim.

Question 4 (Claim Credibility Testing): "If someone told you that [Competitor A's key marketing claim], would you believe them? What would make you sceptical?"

This is extraordinarily useful. It tests whether your competitor's positioning actually lands with buyers. When personas express scepticism about a competitor's claim, you have found a vulnerability. The specific reasons for scepticism become your quick dismiss talking points.

Question 5 (Proof Point Requirements): "What would [your product] need to prove to you to win over [Competitor A]? What evidence would you need?"

This tells you exactly what your sales team needs to bring to competitive conversations: case studies, benchmarks, free trials, integration demonstrations, or security certifications. The gap between what buyers need and what you currently have is your competitive readiness deficit.

Question 6 (Switching Triggers and Barriers): "Have you ever switched from one [category] solution to another? What triggered the switch? What almost stopped you?"

The triggers populate your switching trigger map and inform your outbound timing. The barriers inform your objection handling guide. Together, they tell you when to attack and what to prepare for when you do.

Question 7 (Value vs Premium Positioning): "If you had unlimited budget, which solution would you choose and why? If budget were tight, would your answer change?"

This reveals whether your competitor is winning on perceived value or on price. If personas choose the competitor with unlimited budget but switch to you when budget is tight, you have a value perception problem. If the reverse, you have premium positioning that you can leverage.

From Study to Battlecard: The Claude Code Workflow

The end-to-end workflow proceeds in five phases, each orchestrated by Claude Code:

Phase 1: Competitive Research (5 minutes). Claude Code researches the competitor's website, recent press, product updates, and pricing. It identifies the competitor's stated positioning, their key marketing claims, and any recent changes. This context informs how the seven questions are customised.

Phase 2: Study Design and Recruitment (2 minutes). Claude Code designs the study using the seven-question template above, replacing the bracketed placeholders with the specific competitor and product context. It instructs Ditto to recruit ten personas matching the target buyer profile. Recruitment takes approximately thirty seconds.

Phase 3: Data Collection (5 to 8 minutes). Claude Code submits each question sequentially via the Ditto API, polling for completion between questions. Each persona provides a qualitative, natural-language response. The sequential approach matters: earlier answers provide context for later questions, creating a conversational depth that batched surveys cannot achieve.

Phase 4: Completion Analysis (2 to 3 minutes). Claude Code triggers Ditto's study completion, which generates an automated analysis identifying key segments, divergences, shared mindsets, and suggested follow-up questions. This analysis often surfaces competitive insights that are not obvious from reading individual responses.

Phase 5: Battlecard Generation (10 to 15 minutes). Claude Code synthesises the seventy persona responses (ten personas, seven questions) into the six battlecard sections: Why We Win, Competitor Strengths, Landmine Questions, Quick Dismisses, Switching Triggers, and Recent Wins. The output is a finished, one-page battlecard in customer language, ready for sales distribution.

Total elapsed time: approximately forty-five minutes. Total output: a competitive battlecard that would traditionally require four to six weeks of win/loss interviews, analyst conversations, and PMM synthesis.

What Makes This Different from Monitoring Tools

It is worth being explicit about what Ditto adds to a competitive intelligence stack, because the distinction from existing tools is not immediately obvious.

Klue and Crayon are excellent at what they do. They automate the collection of competitive data: website changes, pricing updates, job postings, press releases, review sentiment. If you are not using a CI monitoring tool, you should be. But monitoring tools answer "what is the competitor doing?" They do not answer "what does the market think about what the competitor is doing?"

Ditto answers the second question. When a competitor launches a new feature, Klue tells you about it. Ditto tells you whether customers care. When a competitor repositions, Crayon tracks the messaging changes. Ditto tells you whether the new positioning lands. When a competitor makes a bold claim on their website, G2 reviews might eventually reflect customer opinion. Ditto gives you that perception data the same afternoon.

The ideal competitive intelligence programme uses both: monitoring tools for continuous Layer 1 and Layer 2 data, and Ditto studies for periodic Layer 3 perception checks. The combination covers all three CI layers.

Quarterly Competitive Tracking: Perception Over Time

A single competitive perception study tells you how the market sees your competitor today. Running the same study quarterly, with fresh persona groups each time, reveals how perceptions are shifting.

Claude Code can orchestrate this as a recurring programme. Each quarter, it runs the same seven questions against a new group of ten personas, then compares the results with previous quarters. The output is a competitive trend report that answers questions like:

Is the competitor's brand association strengthening or weakening?

Are new alternatives emerging that were not mentioned last quarter?

Has the competitor's recent marketing shifted buyer perception?

Are the switching triggers changing? Are new barriers appearing?

Is our win positioning still resonating, or do we need to refresh it?

This kind of longitudinal competitive tracking is, in traditional research terms, prohibitively expensive. Four rounds of win/loss interviews per year, per competitor, is an annual commitment measured in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. With Ditto and Claude Code, it is a quarterly ritual that takes an afternoon.

Multi-Competitor Battlecard Factory

Most product marketers do not face a single competitor. They face three, five, or ten. The competitive battlecard is only useful if it exists for every competitor a sales rep is likely to encounter. This is where the traditional approach collapses entirely. Producing battlecards for five competitors through win/loss interviews and manual research takes months.

Claude Code can run competitive perception studies for multiple competitors in parallel. Each study uses the same seven-question template, customised with the specific competitor's context. Five studies running concurrently against five different Ditto groups produce five finished battlecards in approximately ninety minutes. That is a complete competitive battlecard library, built from primary research data, in a single afternoon.

The studies can also be tailored to different segments. If Competitor A is primarily a threat in the SMB market whilst Competitor B is an enterprise rival, Claude Code runs the Competitor A study against SMB personas and the Competitor B study against enterprise personas. Segment-specific battlecards with segment-specific language.

Connecting CI to the Broader PMM Operating System

Competitive intelligence does not exist in isolation. It feeds directly into several other product marketing functions:

Positioning: competitive alternative maps from CI studies validate (or invalidate) your assumptions about who customers compare you to. If Q1 reveals that buyers think of a competitor you never considered, your positioning needs revision.

Messaging: The language customers use when describing your competitor's strengths becomes the language you need to address in your messaging. The "quick dismisses" from battlecards inform your website copy and ad creative.

Sales Enablement: A single CI study produces enough material for Claude Code to generate not just a battlecard, but also an objection handling guide, a competitive demo script, and a set of discovery questions designed to surface competitive opportunities.

Content Marketing: Competitive perception data is uniquely valuable content. "We asked ten target buyers to compare [Category] tools. Here is what they said" is a blog post that writes itself, backed by primary research no competitor can replicate.

Product Strategy: The "one thing they do poorly" from Q3, aggregated across multiple studies, tells your product team where the market sees genuine gaps. That is roadmap intelligence grounded in buyer perception, not internal assumption.

Limitations and the Hybrid Approach

Synthetic competitive intelligence has clear boundaries. Ditto personas have not used your specific product or your competitor's product. They cannot tell you about specific UX issues, implementation friction, or support quality from firsthand experience. They also cannot tell you about recent competitive deals your team was involved in, because they do not know about them.

The strongest competitive intelligence programmes are hybrid. Ditto provides the continuous baseline: how the market perceives your competitors in general terms, which claims land, which trigger scepticism, what would drive a switch. Real win/loss interviews provide the deal-specific signal: why you lost the Acme Corp deal last month, what the buyer said about the competitor's implementation team, what pricing concession the competitor offered.

The recommended cadence is Ditto studies quarterly for perception tracking plus ongoing win/loss interviews as deals close. Claude Code can maintain the competitive battlecard by updating it with new Ditto study findings each quarter and flagging where win/loss interview data confirms or contradicts the synthetic baseline. The battlecard becomes a living document, continuously refreshed, rather than a static artefact created once and left to decay.

Getting Started

If your sales team is entering competitive conversations with stale battlecards, or worse, with no battlecards at all, this workflow addresses the problem directly. The seven-question study design above has been tested across dozens of competitive studies. The output maps to the standard battlecard format that sales teams already know how to use.

Ditto provides the synthetic research panel. Claude Code orchestrates everything: competitor research, study design, persona recruitment, response collection, insight synthesis, and battlecard generation. The first battlecard takes approximately forty-five minutes. Subsequent cards, with the workflow established, take less.

Sixty-eight percent of your sales opportunities are competitive. The question is not whether your team needs competitive intelligence. It is whether they are getting it fast enough, and in the right format, to actually use it.

This is the third article in a series on using AI agents for product marketing. The first, Using Ditto and Claude Code for Product Marketing, provides a high-level overview. The second, How to Validate Product Positioning with AI Agents, covers positioning validation using April Dunford's framework. Future articles will address messaging testing, pricing research, and the research-to-publication content engine.