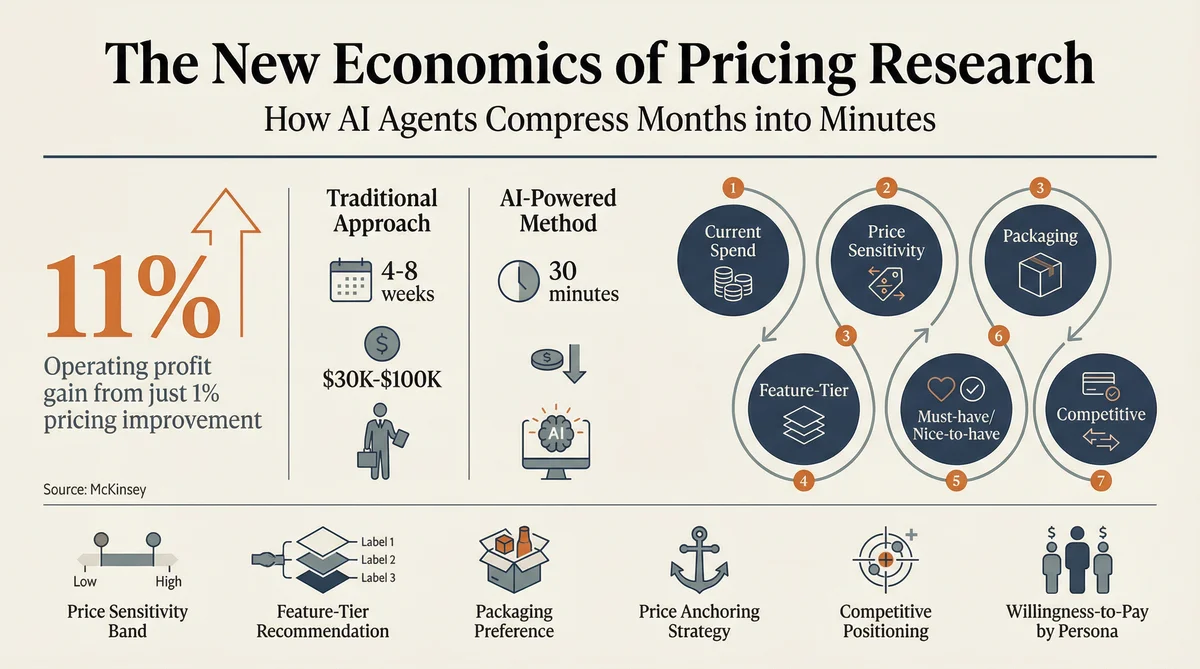

A one percent improvement in pricing yields, on average, an eleven percent improvement in operating profit. That figure comes from McKinsey, and if it strikes you as implausibly large, you are not alone. I did the maths twice. But the logic holds: pricing sits at the top of the revenue equation, multiplied by every unit sold, every renewal cycle, every upsell. A one percent improvement in volume, by contrast, yields only a three to four percent profit gain. Pricing is, by a considerable margin, the most powerful lever most companies never properly pull.

And yet. Ask any product marketing team how they arrived at their current pricing and the answer will frequently involve the phrase "we looked at what competitors charge." Or, more candidly, "our CEO picked a number and we built the tiers around it." Or the classic: "we haven't changed it since launch because the conversation makes everyone uncomfortable."

The discomfort is understandable. Pricing research has traditionally been the domain of specialist consultancies charging six figures for engagements measured in months. Simon-Kucher & Partners built an empire on this exact dynamic. Qualtrics surveys with conjoint analysis modules can take weeks to field and require statistical expertise to interpret. Even lighter-weight approaches like customer interviews suffer from a well-documented problem: people are notoriously unreliable at predicting their own willingness to pay. They tell you what they think you want to hear, anchor to whatever number you mention first, and behave entirely differently when their credit card is actually involved.

This article describes a faster approach. Using Ditto, a synthetic market research platform with over 300,000 AI personas, and Claude Code, Anthropic's agentic development environment, you can run a structured pricing study in thirty minutes, extract willingness-to-pay data, feature-tier preferences, and packaging insights, and produce a set of deliverables that would take a traditional research engagement weeks to compile. It will not replace a full conjoint study for a company making a bet-the-business pricing decision. It will, however, replace the informed guesswork that constitutes the pricing process at most companies.

The Pricing Paradox

Pricing occupies a peculiar position in the product marketing discipline. Every PMM acknowledges its importance. The Product Marketing Alliance's State of Product Marketing report consistently finds that pricing and packaging recommendations are a core PMM responsibility. Pragmatic Institute's framework places pricing as a key strategic output. April Dunford explicitly ties pricing to positioning: your price signals your market category and anchors customer expectations. If you position as premium and price like a commodity, you confuse the market. If you position as accessible and price like enterprise software, you lose trust.

Despite this consensus, most pricing decisions are made with remarkably little customer data. A survey by Price Intelligently (now Paddle) found that the average SaaS company spends only six hours on pricing over the lifetime of the product. Six hours. For the single most impactful revenue lever. The typical process involves an afternoon of competitive benchmarking, a spreadsheet with three columns (Good, Better, Best), and a series of arguments about where to draw the feature lines between tiers.

The reason this matters is not abstract. Pricing errors compound. A product priced ten percent too low leaves money on the table with every transaction. A product priced ten percent too high creates friction that shows up as longer sales cycles, lower conversion rates, and higher churn. And unlike positioning or messaging, which can be tested and adjusted through marketing channels, pricing changes are visible, politically fraught, and often irreversible. Once a customer has seen a lower price, the higher price feels like a betrayal. The cost of getting pricing wrong is not just lost revenue. It is lost trust.

Traditional Pricing Research: Powerful but Impractical

The established approaches to pricing research are genuinely excellent. The problem is that most companies cannot afford them, in either money or time.

The Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter

Developed by Dutch economist Peter van Westendorp in 1976, this technique asks four questions to map a product's acceptable price range: at what price does the product seem too expensive to consider? At what price does it seem so cheap that quality must be compromised? At what price does it start to feel expensive but still worth considering? At what price does it feel like a bargain? The intersection points define the range of acceptable pricing and the optimal price point.

The Van Westendorp model is elegant and has been used for decades across industries. Its limitation is sample size: you typically need at least two hundred responses for statistical reliability, and recruitment takes time. It also struggles with novel products where respondents have no reference point for "too expensive" or "too cheap."

Conjoint Analysis

The gold standard. Conjoint analysis presents respondents with combinations of features and prices, forcing trade-off decisions that reveal implicit willingness to pay for each feature independently. If a respondent consistently chooses a package with Feature A even when it costs more, you know Feature A carries pricing power.

Conjoint is statistically robust and produces granular, actionable data. It is also expensive (typically $30,000 to $100,000 for a full study), technically complex to design, and takes four to eight weeks to field. It requires specialised software and statistical expertise to interpret the results. For large companies making high-stakes pricing decisions, conjoint is worth every penny. For the vast majority of product teams, it is simply out of reach.

Customer Interviews

Cheaper than conjoint, richer than surveys, but plagued by bias. When you ask a real customer what they would pay, they anchor to their current spend, they understate willingness to pay to protect their negotiating position, and they provide socially desirable answers rather than honest ones. A customer who happily pays $200 per month will tell you in an interview that $150 feels fair. Not because they are lying, but because they are negotiating with a future version of you who might raise their price.

The workaround, asking about value rather than price ("what would solving this problem be worth to you?"), produces more useful data but requires skilled interviewers and a substantial sample to identify patterns.

The Seven-Question Pricing Study

This study design adapts elements from Van Westendorp, conjoint, and qualitative pricing interviews into a format that works with Ditto's qualitative persona model. It is not a statistical instrument in the way that conjoint analysis is. It is a structured qualitative study that produces directional pricing data, feature-tier preferences, and packaging insights in thirty minutes.

Claude Code customises the questions with your actual product details, price points, and feature list, then runs the study through Ditto's API against ten personas matching your target buyer profile.

Question 1 (Current Spend Benchmark): "What do you currently spend on [category] solutions per month or year? How do you feel about that price: is it fair, too much, or a bargain?"

This establishes the reference frame. Personas reveal not just what they spend, but how they feel about what they spend. A persona paying $500 per month who describes it as "fair" is in a different mental state from one paying $500 who calls it "painful but necessary." The emotional dimension tells you whether the market is price-sensitive or value-anchored. It also surfaces the competitive pricing landscape as perceived by customers, which may differ significantly from what your competitive analysis spreadsheet shows.

Question 2 (Price Sensitivity and Thresholds): "If [your product] costs [Price A], what is your gut reaction? Now what about [Price B]? At what price would you say 'that is too expensive, I am out'?"

This is the qualitative Van Westendorp. By presenting two specific price points and then asking for the walk-away threshold, you triangulate the acceptable range. The gut reaction matters: "that feels about right" is different from "I'd need to see a lot of proof at that price." The walk-away threshold, combined across ten personas, gives you a ceiling that would be dangerous to exceed without exceptional value justification.

Question 3 (Packaging Preference): "Would you prefer: (a) a free tier with limits, (b) a low-cost plan with core features, or (c) a premium all-in-one plan? Why?"

This question surfaces the fundamental packaging question: freemium versus flat-rate versus tiered. The "why" is the valuable part. A persona who prefers a free tier because "I need to prove value internally before requesting budget" is telling you that your product-led growth motion needs a free tier. A persona who prefers all-in-one because "I hate being nickel-and-dimed" is telling you that your enterprise motion should avoid usage-based pricing. The packaging structure is not a feature decision. It is a go-to-market decision.

Question 4 (Feature-Tier Allocation): "Which of these features would you pay extra for? Which should be included in every plan? [Feature list]"

This is the qualitative analogue of conjoint analysis. Instead of forcing trade-offs through statistical design, you ask directly: what is table-stakes and what is premium? The consensus features that "should be included" are your base tier. The features that personas would "pay extra for" are your upsell candidates. The features that generate blank stares or indifference are the ones you may be over-investing in.

Question 5 (Must-Have Versus Nice-to-Have): "If you could only afford one feature, which would you keep? Which feature, if removed, would make you cancel?"

This separates the vital from the decorative. The feature that personas would keep above all others is your core value driver and should be central to your positioning. The feature whose removal triggers cancellation is your retention anchor and should never be gated behind a premium tier. These two features may or may not be the same, and when they differ, you have learned something important about the gap between acquisition value (what gets them in) and retention value (what keeps them).

Question 6 (Billing Preference): "Annual billing saves twenty percent but locks you in. Monthly billing is flexible but costs more. Which do you prefer and why?"

A seemingly tactical question with strategic implications. Personas who prefer annual billing signal confidence and commitment. Personas who prefer monthly signal uncertainty or a desire to evaluate before committing. The ratio between the two tells you how your GTM motion should handle the billing conversation. If eighty percent prefer monthly, your product needs to demonstrate value quickly enough that the annual conversion happens organically. If eighty percent prefer annual, your sales team should lead with the annual option and use the discount as an incentive rather than a concession.

Question 7 (Competitive Price-Value Trade-off): "A competitor offers [similar product] at [lower price] but without [key differentiator]. Would you switch? What would keep you?"

This is the pricing stress test. You are asking personas to evaluate your pricing power: is your differentiator worth the premium? If personas say yes, your pricing has headroom. If they hesitate, you are closer to the ceiling than you think. The "what would keep you" responses are gold: they tell you exactly what proof points, guarantees, or additional value would justify the price difference. These become your pricing defence arguments for sales conversations.

What Claude Code Produces from a Pricing Study

A completed study yields seventy qualitative responses across seven questions from ten personas. Claude Code analyses these and produces six deliverables:

Price Sensitivity Band. The acceptable price range derived from persona reactions to specific price points and their stated walk-away thresholds. Not a statistically precise number, but a directional range that eliminates the obvious errors (pricing at $99 when personas would comfortably pay $200, or pricing at $500 when personas walk at $250).

Feature-Tier Recommendation. A proposed tier structure showing which features belong in the base plan, which are premium upsell candidates, and which generate insufficient interest to warrant inclusion in any tier. Grounded in persona responses to Questions 4 and 5.

Packaging Preference Breakdown. The split between freemium, flat-rate, and tiered preferences across the persona group, with the qualitative reasoning behind each preference. Directly informs the packaging model decision.

Price Anchoring Strategy. How your pricing should be framed relative to current spend and competitive alternatives, based on the emotional reactions in Questions 1 and 2. If personas describe current spend as 'painful,' your pricing can be positioned as relief. If they describe it as 'fair,' you need to justify the premium through differentiated value.

Competitive Price Positioning. Where your pricing sits in the competitive landscape as perceived by customers, and whether your differentiator justifies the premium (or discount). Based on the competitive stress test in Question 7.

Willingness-to-Pay by Persona. If personas with different demographic or psychographic profiles show different price sensitivity, this analysis maps the variation. A thirty-five-year-old startup founder may have a very different walk-away threshold than a fifty-year-old enterprise procurement manager, even for the same product.

Advanced: Cross-Segment Pricing Research

The basic study tests pricing with one audience. The advanced version reveals how pricing perception varies by segment, which is where most pricing decisions actually get complex.

Claude Code orchestrates three parallel Ditto studies with different persona groups:

Group 1: SMB decision-makers (age 25 to 40, employed). Typically price-sensitive, value flexibility, and need fast time-to-value.

Group 2: Enterprise buyers (age 35 to 55, employed). Less price-sensitive but more process-driven. Care about compliance, support, and scalability.

Group 3: Technical evaluators (filtered by education level: bachelor's degree and above). Care about capability, integration, and technical depth. Price matters less than fit.

Same seven questions. Three audiences. The output is a segment-specific pricing matrix that tells you whether your single pricing page can serve all three segments, or whether you need distinct pricing motions. Often, the answer is the latter: SMB personas want a self-serve entry point at $49 per month, enterprise personas expect to talk to sales and negotiate annual contracts at $500 per month, and technical evaluators want a usage-based model that scales with their needs. The single pricing page with three tiers (Starter, Professional, Enterprise) may be the wrong abstraction entirely.

This has direct implications for product-led sales strategies. If your SMB segment strongly prefers free-tier entry and your enterprise segment expects a sales conversation, you need a hybrid motion. The pricing study does not just inform the numbers on your pricing page. It informs the architecture of how you sell.

Where Pricing Research Fits in the PMM Stack

Pricing is downstream of positioning and messaging, but upstream of go-to-market execution. The sequence matters:

Positioning validation establishes your competitive alternatives, unique attributes, and target customers. Your price is a positioning signal: it must be congruent with how you want the market to categorise you.

Messaging testing validates how to communicate your value. Your pricing page is messaging: the words, the framing, the tier names, the feature comparisons all need to pass the same clarity and resonance tests.

Pricing research validates what the market will pay and how it wants to buy. This determines the commercial model: tiers, packaging, billing cycles, and the pricing defence arguments your sales team will need.

Competitive intelligence provides the context for pricing conversations: where competitors price, what premium your differentiation commands, and what switching costs protect your position.

GTM execution takes the pricing model and distributes it across channels: the self-serve pricing page, the sales-led negotiation playbook, and the expansion revenue strategy for existing customers.

With Ditto and Claude Code, the complete sequence from positioning through validated pricing can be completed in under four hours. Positioning validation (thirty minutes), messaging testing with two rounds (seventy minutes), pricing research (thirty minutes), competitive intelligence (forty-five minutes). The output is a strategic foundation that typically takes a quarter to build through traditional methods.

This does not mean you should rush it. The strategic thinking that happens between each study is as important as the studies themselves. But removing the research bottleneck means the thinking can happen whilst the data is fresh and the decisions are still open, rather than weeks later when the team has already committed to a direction based on assumptions.

Limitations and Where Traditional Methods Still Win

Synthetic pricing research produces qualitative directional data. It tells you that your price is in the right range, that your tier structure makes sense, and that your differentiator justifies a premium. It does not produce the statistical precision of a properly designed conjoint study with two hundred real respondents.

For a venture-backed company raising prices by twenty percent across the board, a thirty-minute Ditto study provides enough signal to make the decision confidently. For a public company restructuring its entire pricing and packaging strategy across multiple product lines and geographies, you want conjoint. The former is a calibration exercise; the latter is a strategic investment. Different questions demand different instruments.

There is also the anchoring question. When you present specific price points in Question 2 ("what if it costs $99? What about $299?"), you are anchoring the persona's response to those numbers, just as you would anchor a real customer in an interview. The mitigation is to test multiple anchoring ranges across separate studies, or to rely more heavily on the open-ended thresholds ("at what price would you walk away?") than the reactions to specific numbers. Claude Code can run two parallel studies with different anchor prices in the same time it takes to run one.

The ninety-five percent correlation between Ditto's synthetic personas and real-world research, validated by EY Americas and in academic studies at Harvard, Cambridge, Stanford, and Oxford, holds for attitudinal and preference research. Pricing sits at the intersection of attitude ("I believe this is worth $200") and behaviour ("I actually paid $200"). The correlation is strong, but real-world validation through A/B pricing tests or controlled rollouts remains the definitive confirmation.

Getting Started

If your pricing was set by looking at competitors and adding a gut feeling, this workflow replaces the gut feeling with data. It will not replace the gut entirely, nor should it: founders and product leaders have contextual knowledge about their market that no research instrument can fully capture. But it eliminates the most common pricing errors: pricing too low because of self-doubt, pricing too high because of aspiration, or, most commonly, not changing pricing at all because the conversation is uncomfortable.

Ditto provides the always-available customer panel. Claude Code handles the orchestration: customising the seven questions with your product details, running the study through Ditto's API, analysing seventy qualitative responses, and producing the six deliverables listed above. Thirty minutes to validated pricing data. The same process through traditional methods takes four to eight weeks and costs more than most startups spend on pricing in their entire lifetime.

McKinsey's eleven percent figure is not a theory. It is arithmetic. The question is not whether pricing matters. It is whether you are willing to spend thirty minutes finding out if yours is right.

This is the fifth article in a series on using AI agents for product marketing. The first, Using Ditto and Claude Code for Product Marketing, provides a high-level overview. The second, How to Validate Product Positioning with AI Agents, covers positioning validation. The third, Competitive Intelligence with AI Agents, covers competitive battlecard generation. The fourth, How to Test Product Messaging with AI Agents, covers iterative message testing. Future articles will address customer segmentation and the research-to-publication content engine.