There is a peculiar tension at the heart of modern marketing. Teenagers represent one of the most valuable consumer demographics on earth - their preferences shape culture, their purchasing power is substantial, and their brand loyalties, once formed, can last decades. And yet, actually researching them has become something of a regulatory minefield.

The reasons for this are sound. Children and adolescents deserve protection from exploitation, and the history of marketing to minors is not exactly covered in glory. But the result is a curious bind: brands desperately need to understand young consumers, whilst the ethical and legal frameworks make direct research increasingly fraught.

I want to explain why this matters, what the actual constraints are, and why synthetic market research offers a genuinely elegant solution to the problem.

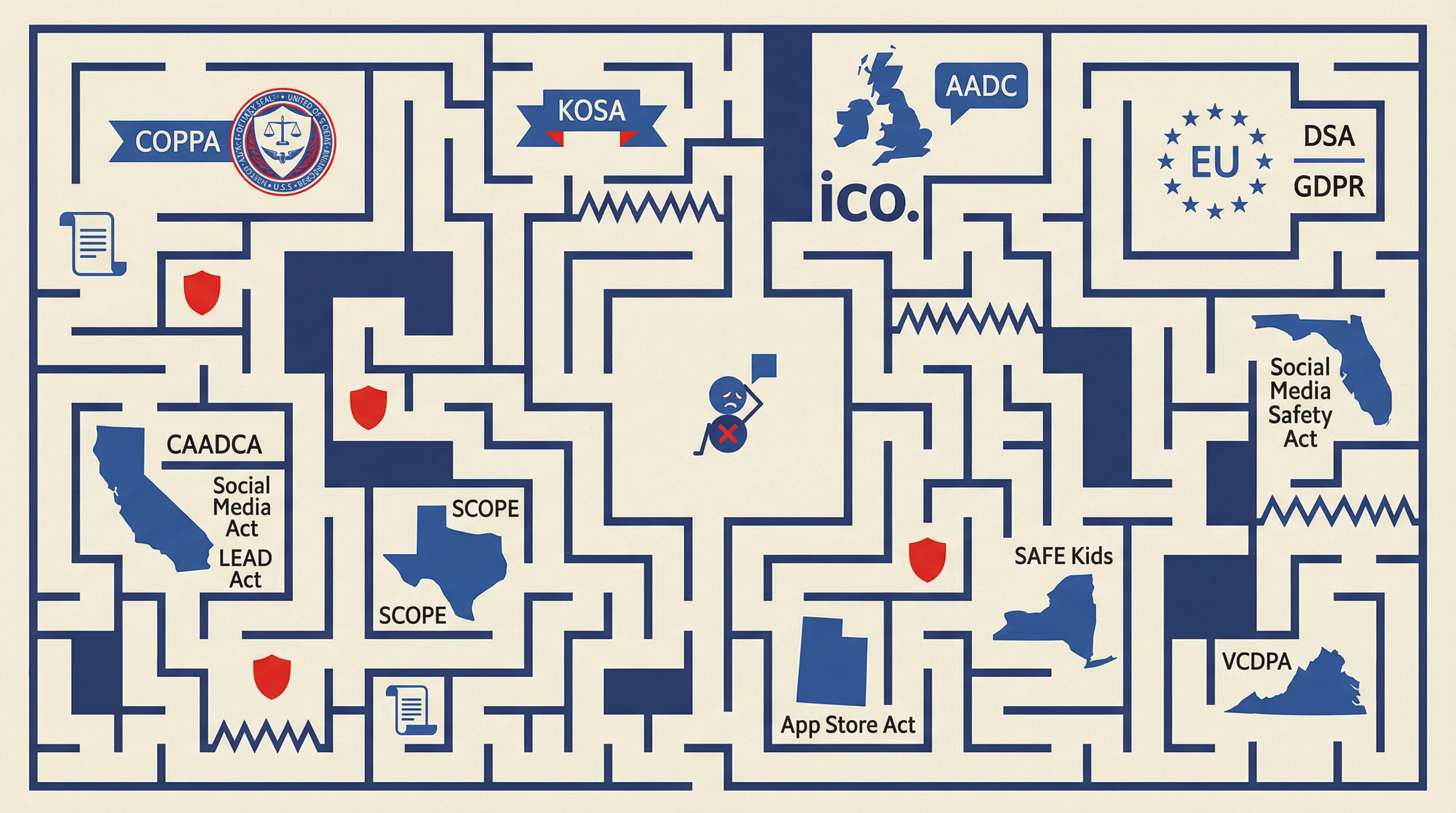

The Regulatory Labyrinth of Teen Market Research

The regulatory landscape around researching minors has grown significantly more complex in recent years. In January 2025, the US Federal Trade Commission finalised comprehensive amendments to COPPA - the first major overhaul since 2013. The changes are substantial: operators must now obtain separate verifiable parental consent before disclosing children's personal information to third parties for targeted advertising, and data retention has been sharply limited.

Across the Atlantic, UK GDPR sets the age of digital consent at 13, with parental permission required for younger children. Companies must make "reasonable efforts" to verify that consent actually comes from someone with parental responsibility - a requirement that sounds sensible until you try to implement it at scale.

The academic world has its own constraints. Institutional Review Boards classify children as a "vulnerable research population" because, as the guidance rather bluntly puts it, "their intellectual and emotional capacities are limited" and they are "legally incompetent to give valid informed consent." Research involving minors seldom qualifies for exempt status, and studies with greater than minimal risk face significant additional scrutiny.

The practical implications are substantial. Researchers working with minors typically need both parental permission and age-appropriate "assent" from the child. For studies spanning different age groups, this might mean developing separate assent forms written at different reading comprehension levels - one for seven to twelve year olds, another for thirteen to seventeen year olds.

And the regulatory tide is flowing in one direction. California's 2024 Protecting Our Kids from Social Media Addiction Act prohibits companies from collecting data on children under 18 without parental consent. Florida's Social Media Safety Act requires age verification and account termination for users under 14. The proposed California LEAD Act would require parental consent before using a child's personal information to train AI models.

Why This Creates a Problem for Brands

None of this is unreasonable. The protection of minors from commercial exploitation is a legitimate societal goal, and the enforcement actions against companies like TikTok and Cognosphere demonstrate these are not merely theoretical concerns.

But here is the bind. Brands still need to understand teen consumers. A clothing retailer cannot simply guess at what fifteen year olds want to wear. A snack company cannot blindly reformulate products without understanding how teenage palates differ from adult ones. A social platform cannot design features in a vacuum.

The traditional solutions are unsatisfying:

Focus groups with parental consent are slow, expensive, and introduce obvious biases. Having your parent sit in the corner whilst you discuss your opinions on energy drinks does something to the authenticity of responses.

Online surveys with verification run into the consent paradox: the very process of obtaining and verifying parental consent creates friction that skews your sample toward highly engaged, permission-granting households.

Observational research - watching what teens actually buy - provides data but no insight into the "why" behind decisions.

Relying on adult proxies - asking parents what their teenagers think - is about as reliable as it sounds.

The Synthetic Alternative for Teen Demographics

This is where synthetic market research becomes genuinely useful rather than merely convenient.

At Ditto, we have built what amounts to a population of synthetic humans - over 300,000 AI-powered personas grounded in census data and behavioural research. These are not generic chatbots generating plausible-sounding responses. Each persona has defined demographics, psychographics, media consumption habits, and behavioural patterns. They respond consistently based on who they are.

When validated against traditional research methods, the correlation is striking. EY found 95% alignment between synthetic responses and real-world research outcomes.

The relevance to teen research should be obvious. A brand wanting to understand how sixteen year olds perceive their messaging can create a research group of synthetic personas matching that demographic profile. They can ask probing questions about purchase motivations, test creative concepts, and explore sensitive topics - all without involving a single actual teenager.

How Synthetic Teen Research Actually Works

The process is straightforward. A researcher defines their target demographic through filters: country, age range, potentially gender or parental status. The system recruits matching synthetic personas from its population.

The researcher then creates a study and asks questions - not yes/no surveys, but open-ended inquiries that invite genuine explanation. "What is your first reaction when you see this advertisement? What appeals to you? What feels off?" The personas respond individually, each filtered through their particular demographic and psychographic profile.

After collecting responses, the system generates analysis: identifying segments, highlighting points of consensus and divergence, and surfacing unexpected insights. The entire process can complete in an afternoon rather than the weeks typically required for properly consented research with actual minors.

The Ethical Case for Synthetic Research on Minors

What makes this approach ethically sound is not merely that it sidesteps the regulatory requirements - though it does. It is that it removes the fundamental ethical tension from the equation.

The core concern with researching minors is the power imbalance. Children and adolescents may not fully understand what they are consenting to, may feel pressure to participate, and cannot meaningfully assess how their data might be used in future. Traditional research attempts to mitigate these concerns through consent frameworks and oversight, but the underlying tension remains.

Synthetic research eliminates it. No actual minor is being researched. No personal data is collected from vulnerable individuals. No child is asked to reveal preferences that might later be used to manipulate them or their peers.

This is not a technicality or a loophole. It is a genuinely different approach that delivers equivalent insights without the ethical costs.

Understanding the Limits

I should be clear about what synthetic research cannot do. It cannot capture genuinely emergent cultural phenomena that have not yet manifested in the training data. It cannot provide the serendipitous insights that sometimes emerge from observing actual humans in unexpected contexts. It cannot replace the value of deep qualitative research with individual participants over extended periods.

For longitudinal studies tracking how the same individuals' views evolve over time, for ethnographic research requiring immersion in actual communities, for questions about phenomena so new they have no historical analogues - traditional methods retain their place.

But for the bread-and-butter questions that drive most commercial research into teen demographics - "How do young consumers perceive our brand?", "What messaging resonates with this age group?", "How should we position this product for the youth market?" - synthetic research delivers robust insights without the ethical overhead.

The Practical Upshot

If you are a brand marketer who has avoided teen research because the consent requirements seemed too onerous, or who has relied on questionable proxies because proper research seemed impossible, the synthetic alternative deserves serious consideration.

The technology exists. The validation is there. The ethical framework is sound. And the practical benefits - speed, cost, depth of insight - are substantial.

Understanding teenagers matters. Doing so ethically matters more. It turns out you can have both.