The Most Expensive Bug Is the One You Ship

In software, the cost of fixing a bug increases exponentially the later you find it. A bug caught in design costs almost nothing. Caught in development, it costs hours. Caught in QA, it costs days. Caught in production, it can cost the company.

Product assumptions work the same way.

An invalid assumption caught during research costs you a few hours and some uncomfortable conversations. The same assumption discovered after launch can cost months of wasted development, burned runway, and a product nobody adopts.

This is what validation and de-risking is about: finding the flaws in your thinking before they become flaws in your product. It's the final checkpoint before committing serious resources. The moment where you actively try to break your own hypothesis.

Most teams skip this step. They've done discovery research. They've tested concepts. They're excited to build. The last thing they want is someone poking holes in their plan.

That reluctance is exactly why this stage matters.

What Validation & De-risking Actually Means

Validation isn't about confirming you're right. It's about discovering where you might be wrong.

The difference is crucial. Confirmation-seeking research asks: "Do people like this idea?" De-risking research asks: "What would stop people from using this, even if they liked it?"

The core questions at this stage:

What assumptions are we making that, if wrong, would kill the product?

What would be an absolute dealbreaker for our target users?

What trust requirements must we meet before users will engage?

What have we assumed about user behaviour that we haven't actually tested?

If this product failed, what would be the most likely cause?

These are uncomfortable questions. They're supposed to be.

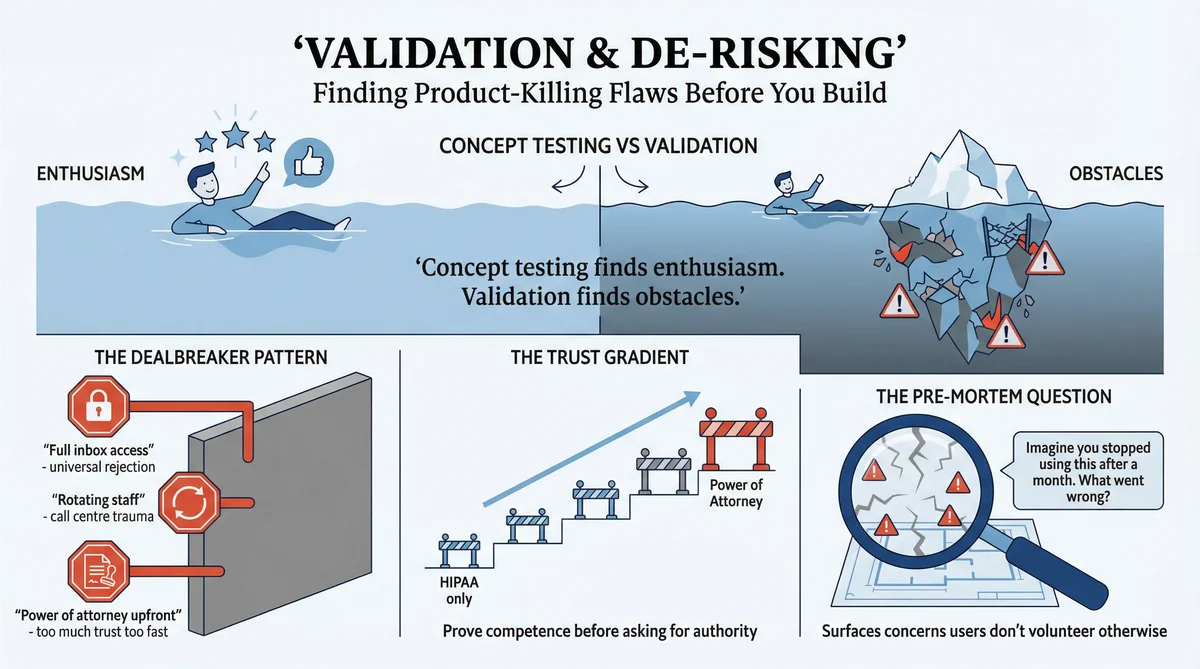

The Difference Between Concept Testing and Validation

Concept testing (Stage 7) asks: "Is this idea appealing?"

Validation asks: "What would prevent adoption even if the idea is appealing?"

A product can test well in concept and still fail catastrophically in practice. Users might love the idea of a service that automatically files flight compensation claims. They might rate it 9/10 for appeal. And then refuse to use it because it requires access they're not willing to grant.

Concept testing finds enthusiasm. Validation finds obstacles.

How to Run Validation Research in Ditto

Ditto is particularly powerful for validation because synthetic personas will tell you uncomfortable truths. They don't worry about hurting your feelings. They don't soften their dealbreakers to be polite. They respond based on who they are and what they would actually do.

Here's how to set up and run a validation study.

Step 1: List Your Assumptions

Before opening Ditto, write down every assumption your product depends on. Be brutally honest. Include:

Access assumptions: What data, permissions, or integrations do you need?

Behaviour assumptions: What actions do you expect users to take?

Trust assumptions: What must users believe about you?

Switching assumptions: Why would users leave their current solution?

Value assumptions: What makes this worth the effort?

For the flight compensation startup, the assumption list included: users will grant email inbox access, 30% fee is acceptable, users trust an unknown startup with sensitive data, and automatic filing is preferred over manual.

Rank each assumption by potential damage: if this is wrong, does it kill the product or just require adjustment?

Step 2: Design Your Research Group

In Ditto, create a research group that matches your target user. For validation, precision matters more than breadth. You want people who would actually use this product.

Example: Flight compensation validation study

Name: "Frequent Travellers - Privacy Conscious" | Size: 10 personas | Filters: Country US/UK, Age 25-55, Employed

Example: CareQuarter validation study

Name: "Adult Children Managing Elder Care" | Size: 10 personas | Filters: Country US, Age 45-65, Has living parents

The key is matching the demographic profile you've been researching. Validation should stress-test with the same audience, not a different one.

Step 3: Write Validation-Specific Questions

Validation questions are different from discovery questions. You're not exploring the problem. You're stress-testing your solution.

The 7-Question Validation Framework:

1. Assumption testing: "I'm going to describe a product. [Describe it clearly.] What's your initial reaction? What concerns come to mind immediately?"

2. Dealbreaker identification: "What would be an absolute dealbreaker that would make you never use this, no matter how good the benefits?"

3. Trust requirements: "What would you need to see, hear, or verify before trusting this product with [sensitive action]?"

4. Specific assumption probe: "This product requires [specific requirement]. How do you feel about that? Would you grant it?"

5. Objection surfacing: "What concerns would you have about using this? What would make you hesitate?"

6. Risk perception: "What could go wrong if you used this product? What's the worst case scenario you can imagine?"

7. Pre-mortem: "Imagine you tried this product and stopped using it after a month. What do you think went wrong?"

Step 4: Run the Study and Watch for Patterns

In Ditto, submit your questions and wait for responses. Each persona responds independently based on their characteristics.

What to look for in responses:

Unanimous rejection: If 9/10 personas reject something, that's a dealbreaker

Conditional acceptance: "I would if..." responses show you the path forward

Specific past experiences: "I once had..." responses predict future behaviour

Emotional intensity: Strong language ("absolutely not," "no way") signals hard limits

Suggested alternatives: When personas reject your approach but offer what they'd accept instead

When asked about email access, 8/10 personas used strong rejection language. But the same personas offered alternatives: "If I could just forward specific emails..." This pattern revealed: the value proposition worked, but the implementation was wrong.

Step 5: Use Ditto's Completion Analysis

After all questions are answered, complete the study in Ditto. The platform generates AI analysis including:

Key Segments: Groups of personas who responded similarly. Example: "Privacy-First Users" - Tech-savvy, aware of data risks. Insight: Unanimously rejected full inbox access, but open to scoped alternatives.

Divergences: Where personas disagreed. Example: Fee Sensitivity - Some said 30% is reasonable, others felt it was too much for an automated process.

Shared Mindsets: Universal truths across all personas. Example: "Trust must be earned progressively" - All personas wanted to see competence before granting broader access.

These AI-generated insights save hours of manual analysis and often surface patterns you'd miss reading responses individually.

Step 6: Create Your Validation Summary

Translate Ditto's findings into actionable decisions. Your summary should include: assumptions tested (validated or invalidated with evidence), dealbreakers identified with supporting quotes, trust requirements, and product changes required. End with a clear PROCEED / PIVOT / STOP decision.

Using Claude Code to Orchestrate Validation Research

Claude Code can manage the entire validation workflow, from assumption inventory through risk assessment. The combination of Claude Code's orchestration capabilities with Ditto's synthetic research creates a powerful de-risking system.

Phase 1: Assumption Inventory

Claude Code begins by systematically extracting assumptions from your product documentation, previous research, and stated plans. Give Claude Code your product spec or pitch deck and ask it to identify:

Implicit assumptions about user behaviour

Required permissions or data access

Trust prerequisites that must be met

Switching costs you're asking users to bear

Value propositions that haven't been tested

Claude Code will rank these assumptions by damage potential. Assumptions that would kill the product if wrong get tested first.

Phase 2: Validation Study Design

With assumptions identified, Claude Code designs the validation study in Ditto:

Creates a research group matching your target demographic

Translates each high-risk assumption into a probing question

Structures the 7-question validation framework around your specific risks

Includes the pre-mortem question to surface hidden concerns

Claude Code calls the Ditto API to create the research group and study, then submits the questions and monitors for completion.

Phase 3: Pattern Analysis

As responses arrive, Claude Code analyses them for:

Dealbreaker signals: Absolute language ("never", "no way") vs conditional language ("I would if...")

Trust requirements: What credentials, proof, or progressive access users demand

Alternative suggestions: When users reject your approach but offer what would work

Segment differences: Where different persona types have different concerns

When Ditto's completion analysis runs, Claude Code synthesises it with individual response patterns to build a comprehensive risk map.

Phase 4: Risk Mitigation Output

Claude Code delivers structured validation output:

Assumption validation matrix (validated/invalidated with evidence)

Dealbreaker inventory with supporting quotes

Trust ladder design (minimum viable trust to start, progression path)

Required product changes before launch

Go/pivot/stop recommendation with reasoning

Example Prompt for Claude Code

Run validation research for my product: [describe product]. The core assumptions I need to test are: [list 3-5 assumptions]. Create a validation study with 10 personas matching [demographic]. Use the 7-question validation framework. Flag any dealbreakers and trust requirements. Recommend whether to proceed, pivot, or stop based on findings.

Claude Code handles the API calls to Ditto, monitors the study, analyses responses, and delivers a validation summary you can act on immediately.

The Four-Hour Validation Sprint

With Claude Code orchestrating and Ditto providing synthetic research, you can complete a validation sprint in a single afternoon:

Hour 1: Assumption extraction and prioritisation

Hour 2: Research group creation and question design

Hour 3: Study execution and response collection

Hour 4: Analysis and validation summary generation

This compresses what traditionally takes weeks into a focused session. The faster you find fatal flaws, the less you invest in building the wrong thing.

Case Study: CareQuarter's Trust Architecture

CareQuarter had validated their problem (Phase 1) and confirmed the concept appealed to their target market. Adult children managing elder care wanted help. They were willing to pay. The concept tested well.

But CareQuarter's service required something sensitive: authority to interact with healthcare providers on behalf of someone's ageing parent. That's not a small ask. Before building, they needed to understand exactly what trust requirements users would demand.

The Validation Study Design

Phase 2 recruited 10 additional synthetic personas with the same demographic profile. Seven new questions explored:

What "authority" means in practice (HIPAA vs. power of attorney vs. spending authority)

Trust prerequisites for granting access to medical records

Dealbreakers that would kill the relationship

Communication preferences (frequency, channel, level of detail)

Trigger moments that would prompt someone to seek help

What the Research Revealed

Trust architecture emerged as the critical design constraint.

The findings weren't about whether users wanted the service. They did. The findings were about the specific conditions under which they would actually use it.

1. Start with HIPAA only. Power of attorney is too much trust too fast.

Users wanted to see competence before granting broader authority. HIPAA authorisation allows the coordinator to talk to providers but not make medical decisions. Asking for power of attorney upfront would kill conversions.

2. Named person, not a team.

Every persona rejected the concept of a rotating care team. They'd been burned by anonymous call centres. They wanted a single named coordinator who knew their family's situation.

"I've explained my mother's situation to a dozen different people. I'm not doing that again."

3. Phone and paper first.

The target demographic actively rejected app-based solutions. They already had too many portals, too many logins, too many notifications. Phone calls and mailed summaries were the preferred interaction model.

4. Guardrails are non-negotiable.

Spending caps, defined scope, easy exit, clear documentation of what the coordinator can and cannot do. Control wasn't a nice-to-have; it was a prerequisite for any engagement.

The Dealbreakers

The study surfaced specific conditions that would immediately disqualify the service:

Rotating or anonymous staff: "If I have to re-explain everything each time, what's the point?"

No spending caps or unclear billing: "I'd never sign up without knowing my maximum exposure"

Data resale or marketing reuse: "Absolutely not. This is my mother's health information."

Complicated cancellation process: "Red flag. If it's hard to leave, I won't start."

Coordinator who recommends but doesn't execute: "I don't need more advice. I need someone to actually DO things."

What This Changed

Without this validation study, CareQuarter might have:

Asked for power of attorney at signup (killing conversions)

Built a rotating team model (triggering the "call centre" association)

Prioritised an app (which their demographic would reject)

Offered "advisory" services (when users wanted execution)

Each of these would have been a reasonable assumption. Each would have significantly damaged adoption. The validation study caught all of them before a single line of code was written.

View the CareQuarter Phase 2 study

Case Study: The Inbox Access Dealbreaker

A flight compensation startup was building an AI service that would scan users' email inboxes to find delayed flight confirmations and automatically file compensation claims. The value proposition was compelling: money you're owed, recovered automatically, with zero effort on your part.

The business model was straightforward: 30% of recovered compensation. Users would get money they'd never have claimed otherwise. The startup would take a cut for doing the work.

Concept testing showed strong interest. The idea of "free money for zero effort" resonated. Users rated appeal highly.

But the service had a core requirement: it needed to scan the user's email inbox to find flight confirmations.

The Assumption That Nearly Killed the Product

The founders assumed users would grant inbox access in exchange for the value provided. After all, people grant inbox access to email clients, calendar apps, and various productivity tools. This seemed like a reasonable trade.

They ran a validation study in Ditto before building. Ten personas. Seven questions focused on the privacy tradeoff, adoption barriers, and trust requirements.

What the Research Revealed

"Full inbox access" was a near-universal dealbreaker.

Not "some concerns." Not "would need reassurance." A hard no from almost every participant.

"My inbox has everything - work emails, personal messages, financial statements. No way I'm giving a random app access to all of that."

"Even if the app promised not to read anything except flight confirmations, how would I know? I'd have to trust them completely."

"This feels like giving someone the keys to my house so they can water one plant."

The 30% fee was acceptable. The value proposition was compelling. Users wanted the service. But the access requirement was a wall they wouldn't climb.

The Pivot That Saved the Product

The validation study didn't just identify the problem. It surfaced acceptable alternatives. When asked what would make them comfortable, participants described several options:

Folder-only access: "If I could create a 'Travel' folder and only give access to that, maybe"

Read-only OAuth with limited scope: "If it could only see emails from airlines, that's different"

One-time scan: "Let me upload specific emails rather than giving ongoing access"

Manual forwarding: "I'd forward flight confirmations to a special email address"

The research revealed that users weren't opposed to the service. They were opposed to the specific implementation. The founders could deliver the same value with a different technical approach that respected users' privacy boundaries.

Without this validation study, they would have built a product with a fatal adoption barrier baked into its core architecture. The engineering would have been wasted. The launch would have failed.

The Pre-Mortem Technique in Ditto

One of the most powerful validation techniques is the pre-mortem: imagining your product has failed and working backwards to understand why.

Traditional post-mortems happen after failure. Pre-mortems happen before launch.

The question: "Imagine you tried this product and stopped using it after a month. What happened? What went wrong?"

This framing gives synthetic personas permission to be negative. It surfaces concerns that might not emerge in direct questioning.

How to Use Pre-Mortems in Ditto

Add this as your final question in any validation study: "Imagine you signed up for [product], used it for a few weeks, then stopped and deleted it. What went wrong? What made you quit?"

Ditto's personas will generate scenarios based on their characteristics. Privacy-conscious personas imagine data breaches. Busy professionals imagine time-wasting complexity. Budget-conscious personas imagine hidden costs.

Pre-Mortem Responses from the Flight Compensation Study

When asked to imagine why they'd abandoned the service, personas generated a list of concerns:

"The app got hacked and my emails were exposed"

"They started sending me spam or selling my data"

"It filed a claim wrong and I got in trouble with the airline"

"The 30% fee seemed fine until I saw how much they took from a big claim"

"I forgot I'd signed up and panicked when I saw it accessing my email"

"They went out of business and I had no idea what happened to my data"

Several of these concerns hadn't surfaced in direct questioning. The pre-mortem framing unlocked them.

Interpreting Ditto's Validation Outputs

After completing a validation study, Ditto provides several analytical layers:

Individual Responses: Read each persona's answers carefully. Look for absolute language ("never," "absolutely not" = hard dealbreaker), conditional language ("I would if" = negotiable concern), and past experience references ("I once had" = strong predictor).

AI-Generated Segments: Ditto identifies groups with similar responses. Use these segments to design your trust ladder - how you'll move users from skeptical to committed.

Divergences: When personas disagree, you've found a segmentation opportunity. You may need to support both preferences, or choose which segment to prioritise.

Shared Mindsets: Universal truths that apply across all personas become non-negotiable product requirements.

What Validation Research Reveals

Across multiple validation studies, certain patterns emerge consistently:

1. The "Obvious" Assumption That Isn't

Almost every validation study surfaces at least one assumption that founders considered obvious but users reject. The flight compensation startup assumed inbox access would be acceptable. CareQuarter could have assumed users would want an app.

Lesson: List your assumptions explicitly. Then test them in Ditto. Especially the ones that feel too obvious to question.

2. The Trust Gradient

Users rarely trust all at once. They want to see competence before granting authority. CareQuarter learned to start with HIPAA authorisation before asking for power of attorney. The flight compensation startup learned that limited, scoped access was acceptable while full access was not.

Lesson: Design for progressive trust. Use Ditto to find the minimum viable trust level where users will start.

3. The Specificity of Dealbreakers

Dealbreakers are rarely abstract. They're specific and often based on past experience. "I've been burned by anonymous call centres." "I once signed up for something and couldn't cancel."

Lesson: Probe for specific past experiences. Ditto's personas draw on realistic backgrounds that generate these specific concerns.

4. The Alternatives Users Suggest

When users reject an approach, they often suggest alternatives. "I won't give full inbox access, but I'd forward specific emails." These suggestions show you how to deliver value within users' actual constraints.

Lesson: When Ditto personas hit a wall, note what they say would work instead. The pivot is often right there in the response.

Quick Reference: Validation in Ditto

Step 1: Preparation

List all assumptions your product depends on. Rank by potential damage if wrong. Identify specific questions to test each assumption.

Step 2: Research Group

Create group matching your target user. 10 personas is typical for validation. Use same demographic filters as earlier research.

Step 3: Questions

Use the 7-question validation framework: Initial reaction, dealbreakers, trust requirements, specific assumption probes, objections, risk perception, pre-mortem.

Step 4: Analysis

Read individual responses for absolute vs conditional language. Review AI-generated segments. Note divergences (segmentation opportunities). Identify shared mindsets (universal requirements).

Step 5: Decision

Translate findings into assumption validation list. Compile dealbreakers and trust requirements. Make go/pivot/stop decision.

How This Feeds Into the Next Stage

Validation and de-risking is the final research gate before significant development investment. If you pass this stage with your assumptions intact (or appropriately modified), you have strong evidence that your product will succeed in the market.

The next stage, Launch Research, shifts focus from "will users adopt?" to "what will their first experience be like?" You'll anticipate onboarding friction, design feedback mechanisms, and prepare for the transition from research to reality.

Explore the Research

The CareQuarter validation study is publicly available:

CareQuarter Phase 2: Trust Deep Dive - 10 personas on trust requirements and dealbreakers

Ready to validate your assumptions before you build? Learn more at askditto.io