Survivorship bias is the logical error of focusing on things that made it past some selection process while ignoring the things that didn't. It makes success look simple and failure invisible. And it's probably distorting half the business decisions you make.

The Classic Example: Where Not to Armor the Bomber

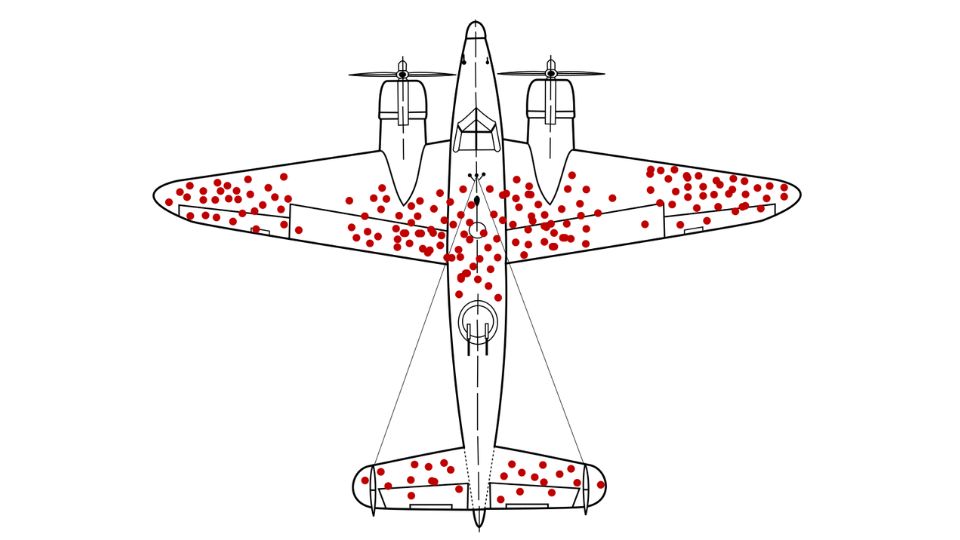

During World War II, the U.S. military studied bombers returning from combat missions to figure out where to add armor. The planes that made it back had bullet holes clustered around the wings and tail. The obvious answer seemed to be: reinforce those areas.

Statistician Abraham Wald looked at the same data and reached the opposite conclusion. The planes they were studying had survived despite being hit in those locations. The planes that got hit in other areas—the engines, the cockpit—never made it back to be studied. Those were the spots that needed armor.

The military was only looking at survivors. The data from the planes that went down was gone.

Why This Matters for Every Business Decision

Survivorship bias shows up constantly in business research because you can only study what still exists.

Product Development

You survey customers about which features they value most. But you're only hearing from people who stuck around. The customers who tried your product and bounced aren't in your dataset anymore. Their absence is telling you something, but you can't hear it.

A SaaS company looks at power users to understand what drives engagement. Those users love the advanced features. The company builds more advanced features. Six months later, new user activation is down 20%. Turns out the features that keep power users engaged are precisely what overwhelms new users during onboarding. The failed new users never made it into the analysis.

Customer Research

You analyze purchase patterns of your most loyal customers to understand what builds loyalty. But customers who churned last quarter aren't in the loyalty segment anymore. Whatever drove them away doesn't show up in the data about what drives loyalty.

A coffee chain studies its rewards program members to understand customer preferences. Members love the specialty drinks and seasonal offerings. The chain expands the menu and adds more premium options. But most customers never joined the rewards program in the first place because they just wanted fast, simple coffee. Sales decline because the company optimized for the wrong segment.

Marketing Performance

You look at which campaigns drove the most conversions among active customers. But you don't see the campaigns that drove people away, unsubscribed them, or made them tune out your brand. Those people disappeared from your measurement pool.

Startup Strategy

Entrepreneurs study successful companies to figure out what works. Every successful startup pivoted at least once. Every successful founder was told no by dozens of investors. The lesson seems clear: persistence and willingness to pivot are keys to success.

But this ignores the thousands of failed startups whose founders also persisted and pivoted repeatedly. Those failures aren't in the dataset of companies people study. Persistence might be necessary, but the data doesn't tell you if it's sufficient.

The Problem With Learning From Success

Success stories are everywhere. Failed attempts disappear. This creates an asymmetry in what you can observe.

When a new product launch works, everyone studies it. When it fails, it gets quietly discontinued and memory-holed. The failed launch playbooks don't get written. The case studies don't get published. The lessons stay locked inside the companies that experienced them.

This makes success look more replicable than it is. You see ten companies that succeeded using strategy X. You don't see the hundred companies that tried strategy X and failed because they're no longer around to study.

How Traditional Research Tries to Handle It

Intentional Failure Analysis

Some companies make a point of documenting and studying failures. Post-mortems, lessons learned databases, internal case studies of what didn't work. This requires discipline and a culture that doesn't punish failure, which is rare.

Cohort Analysis

Track everyone who started in a given time period, not just who's still around. If you signed up 1000 users last quarter, track all 1000 even as they churn. This lets you see the full distribution, not just the survivors. But it requires infrastructure to track people after they leave.

Control Groups and Experiments

Randomly split your population and try different approaches. Track both groups over time. This lets you see who drops out under different conditions. But running clean experiments is expensive and many companies don't have the traffic or patience to wait for statistical significance.

Exit Interviews and Churn Surveys

Ask people why they left. The problem is most people don't respond. The ones who do respond aren't representative of all churned users. You're sampling from survivors again, just one level deeper.

The Challenge: Most Failures Leave No Data

The ideal solution would be to study both successes and failures equally. But failures often don't leave enough data behind to study.

Customers who bounced after one session. Products that got killed in beta. Campaigns that got pulled early. Markets you decided not to enter. These don't generate the data volume you need for robust analysis.

By the time you realize you need to study the failures, the failures are already gone.

A Different Approach: Modeling the Counterfactual

Traditionally, you can't study what didn't happen or what no longer exists. Synthetic research approaches let you explore counterfactuals before the actual selection process happens.

Instead of waiting to see which customers churn and trying to study the survivors, you can model how different customer segments would likely respond to different product directions. This includes modeling the customers who would leave, before they actually leave and disappear from your data.

You can simulate what would happen if you pursued strategy A versus strategy B, including who would stick around and who wouldn't. The failures don't have to happen in the real world to learn from them.

This doesn't replace cohort analysis or learning from real failures. But it lets you explore the space of possible failures before committing resources, so you can test whether survivorship bias is likely to mislead you in a specific decision.

How Synthetic Research Models the Full Population

Survivorship bias is a sampling problem. Traditional research can only interview people who show up—customers who didn't churn, product trials that didn't fail immediately, businesses still in operation. The silent majority who quit, failed, or walked away never make it into your dataset.

Synthetic research approaches this differently. Instead of recruiting from surviving populations, it models the entire demographic structure from census data and behavioral datasets that capture both survivors and non-survivors. When you query synthetic personas about a product category, you're not just hearing from current users. You're modeling the full population including people who tried and quit, considered but never bought, and never engaged at all.

The Ditto methodology calibrates approximately 320,000 synthetic personas to Census Bureau microdata, preserving realistic distributions of income, employment, household structure, and life circumstances that correlate with product adoption and abandonment. This population-true foundation means your synthetic sample includes the struggling single parents who can't afford premium products, the rural households without delivery access, and the time-constrained professionals who bought once but never repurchased—segments that traditional recruitment systematically misses.

This matters most for understanding failure modes. Why did that product launch underperform projections? Traditional research interviews enthusiasts who loved it. Synthetic research models the skeptics who ignored it, the price-sensitive shoppers who considered then rejected it, and the target demographic that never noticed it existed. The full population perspective reveals what survivors-only data obscures.

The practical advantage: you can test concepts against realistic market distribution before launch, modeling both early adopters and resistant segments simultaneously. Traditional research shows you the best-case scenario (people willing to take your survey). Synthetic research models the actual market, survivors and all.