If you've been around the hydration aisle lately, you've probably seen DripDrop making bold claims. "Medical-grade" hydration. "Doctor-developed." "Used in disaster relief." The messaging is everywhere — and it sounds IMPRESSIVE. But here's the question that keeps me up at night: do everyday consumers actually care?

We ran a study with 6 American consumers to find out. And honestly? The results were a proper reality check.

The Research Setup

We assembled a diverse group of US consumers aged 25-65 — the kind of people who might actually reach for a hydration product at the supermarket or pharmacy. Not health fanatics, not marathon runners. Just regular folks who sometimes feel a bit dehydrated.

We asked them three questions:

What's your honest reaction to DripDrop's "medical-grade" positioning? Does it make you MORE or LESS likely to buy?

When you're feeling dehydrated, what do you actually reach for? Be honest about your habits.

DripDrop costs roughly 3x more than Gatorade. What would make that premium worth it to you — or is it simply too much?

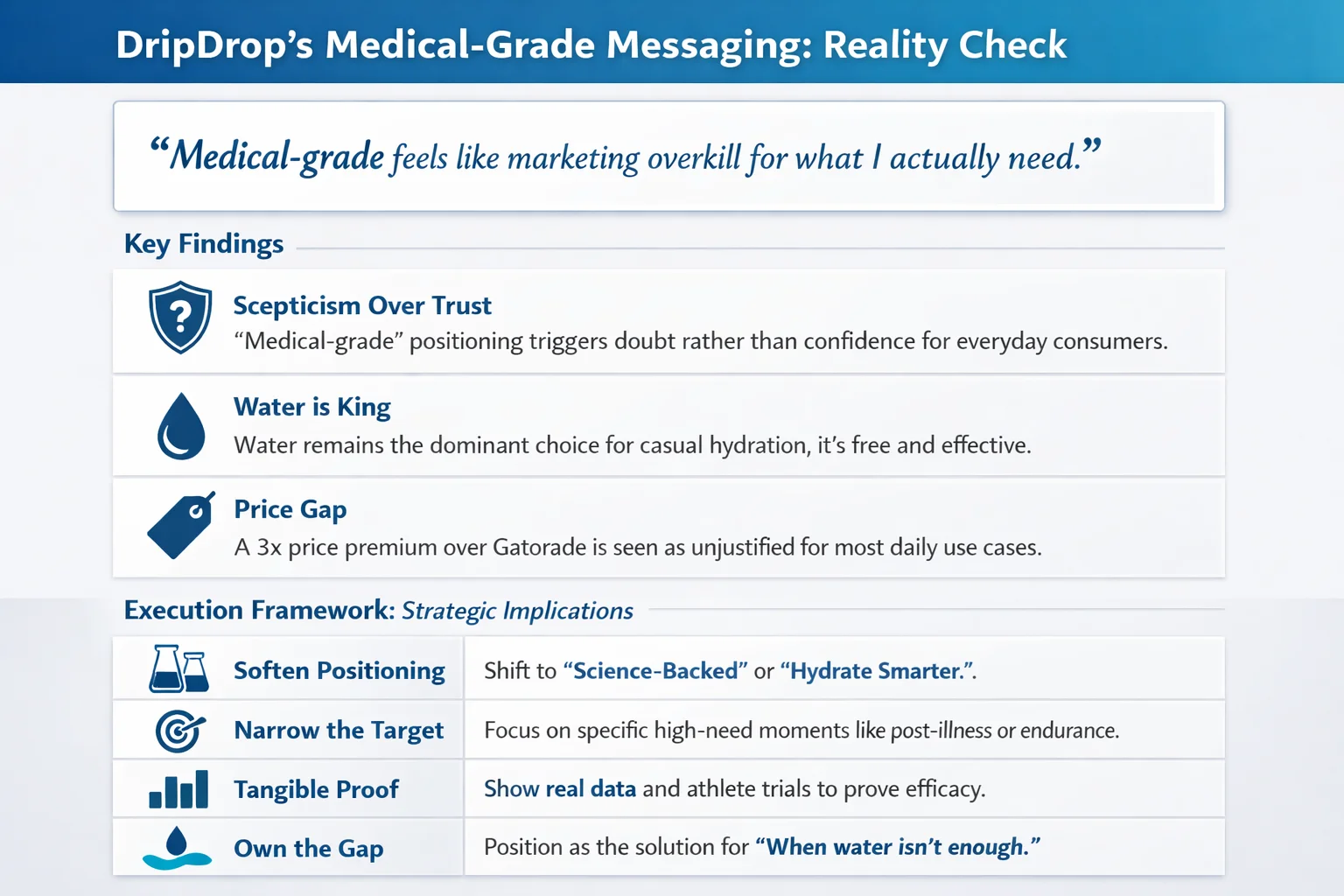

Finding #1: "Medical-Grade" Triggers Scepticism, Not Trust

This was the big one. We expected consumers to be impressed by the medical credentials. After all, DripDrop was literally developed by a doctor for use in humanitarian crises. That's a genuine origin story.

But consumers saw it differently.

"Medical-grade feels like marketing overkill for what I actually need," one participant told us. "I'm mildly dehydrated after a jog, not recovering from cholera."

Another was even more blunt: "You can't hydrate on a press release."

The pattern was clear: for everyday hydration needs, "medical-grade" doesn't translate to "better." It translates to "overkill" — and potentially "overpriced." Consumers felt like they were being sold a solution to a problem they didn't have.

Finding #2: Water Wins. Full Stop.

When we asked what people actually reach for when dehydrated, the answer was gloriously simple: water.

Not electrolyte solutions. Not sports drinks. Not coconut water or fancy hydration powders. Just... water. From the tap. Free.

"I drink water when I'm thirsty," one participant said, as if stating the obvious. "Why would I pay for something with chemicals when water exists?"

Some mentioned Gatorade for after intense workouts, but even then it was situational — not a daily habit. The hydration category faces a fundamental challenge: water is free, effective, and has zero marketing skepticism attached to it.

For DripDrop to win, they need to convince consumers that water ISN'T enough. That's a hard sell when water has worked perfectly well for millennia.

Finding #3: The Price Premium Is a Bridge Too Far

DripDrop costs roughly 3x what Gatorade costs. We wanted to understand what would justify that premium — if anything could.

The consensus? Not much.

"If I'm sick enough to need medical-grade hydration, I'm going to the doctor," one participant said. "If I'm just a bit thirsty, I'm not paying premium prices."

The problem is positioning. DripDrop sits in an awkward middle ground: too expensive for casual hydration, too accessible for true medical need. Consumers who are genuinely dehydrated (flu, food poisoning, marathon) might buy it — but that's a small, infrequent market. Everyone else is reaching for water or the cheaper alternative.

Interestingly, some participants said they MIGHT pay the premium if they saw tangible proof — faster recovery, better taste, something measurable. "Give me a reason beyond marketing speak," one said.

The Strategic Implications

So what should DripDrop do with this feedback? Here's what the research suggests:

1. Rethink the "medical-grade" positioning — For everyday consumers, it creates more scepticism than trust. The disaster relief credentials are impressive but irrelevant to someone who's just had a tough gym session. Consider softer positioning: "Science-backed hydration" or "Hydrate smarter" might land better.

2. Narrow the target audience — Stop trying to be everything to everyone. Focus on specific use cases where electrolyte replacement genuinely matters: post-illness recovery, endurance athletes, travel to hot climates, hangover recovery (there, I said it). Own those moments completely.

3. Show, don't tell — Consumers want proof, not claims. Partner with fitness trackers, run visible trials, get athletes to show real recovery data. Make the science tangible.

4. Address the elephant in the room — Water is the competition. Acknowledge it. "When water isn't enough" could be a positioning angle that's honest about the limited use case while owning it confidently.

The Bigger Picture

This research highlights a common trap in CPG marketing: impressive credentials don't automatically translate to consumer appeal. DripDrop has a genuine story — doctor-developed, used in cholera treatment, backed by real science. But that story was built for humanitarian contexts, not retail shelves.

The messaging needs to evolve for the everyday consumer. Less "medical-grade," more "works better than water when you really need it." Less disaster relief credentials, more relatable moments of need.

The product itself isn't the problem. The positioning is.

Want to Test Your Own Messaging?

This study took us about 15 minutes to run — from question design to actionable insights. If you're curious how your brand's positioning lands with real consumers, Ditto can help you find out before you commit to expensive campaigns.

Sometimes the most valuable insight is discovering what ISN'T working — before you scale it.